The Salem Witch Trials

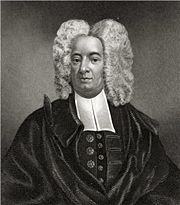

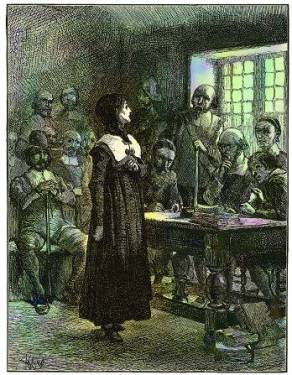

1876 illustration of the courtroom; the central figure is

usually identified as Mary Walcott

The Salem witch

trials were a series of hearings before local magistrates followed by

county court trials to prosecute people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts,

between February 1692 and May 1693. Over 150 people were arrested and imprisoned,

with even more accused who were not formally pursued by the authorities. The

two courts convicted twenty-nine people of the capital felony of witchcraft. Nineteen

of the accused, fourteen women and five men, were hanged. One man who refused

to enter a plea was crushed to death under heavy stones in an attempt to force

him to do so.

Background

In 1689, Salem Village

was finally allowed by the church in Salem Town to form their own separate

covenanted church congregation and ordain their own minister, after many

petitions to do so. Salem Village was torn by internal disputes between

neighbours who disagreed about the choice of Samuel Parris as their

first ordained minister, and about the choice to grant him the deed to the

parsonage as part of his compensation.

Increasing family size

fuelled disputes over land between neighbours and within families, especially

on the frontier where the economy was based on farming. Changes in the weather

or blights could easily wipe out a year's crop. A farm that could support an

average-sized family could not support the many families of the next

generation, prompting farmers to push farther into the wilderness to find land,

encroaching upon the indigenous people. As the Puritans had vowed to create

a theocracy in this new land, religious fervour added tension to the

mix. Loss of crops, livestock, and children, as well as earthquakes and bad

weather, were typically attributed to the wrath of God.

Rev.

Cotton Mather (1663-1728)

Despite reverence for

the Bible and antipathy towards "Popery," the Puritans had

established a type of theocracy akin to that of medieval Roman Catholicism, in

which the church ruled in all civil matters, including that of administering

capital punishment for violations of a spiritual nature.

The Puritans believed in the existence of an invisible world inhabited by God

and the angels, including the Devil (who was seen as a fallen angel) and his

fellow demons. To Puritans, this invisible world was as real as the visible one

around them.

In his book Memorable

Providences Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions (1689), Cotton

Mather describes strange behaviour exhibited by the four children of a

Boston mason, John Goodwin, and attributed it to witchcraft practiced upon them

by an Irish washerwoman, Mary Glover. Mather was a prolific publisher of

pamphlets and a firm believer in witchcraft.

The Puritans believed

that men ought to rule over women, and that women need to be totally

subservient and subordinate to men. This is known as “patriarchy.” The

Puritans thought that, by nature, a woman was more likely to enlist in the

Devil's service than was a man, and women were considered lustful by nature.

In addition, the small-town atmosphere made secrets difficult to keep and

people's opinions about their neighbours were generally accepted as fact. In an

age where the philosophy "children should be seen and not heard"

was taken at face value, children were at the bottom of the social ladder. Toys

and games were seen as idle and playing was discouraged. Girls had

additional restrictions heaped upon them. Boys were able to go hunting,

fishing, exploring in the forest, and often became apprentices to carpenters

and smiths, while girls were trained from a tender age to spin yarn, cook, sew,

weave, and be servants to their husbands, mothers, and children.

Most timelines of the

Salem Witch Trials begin with the afflictions of the girls in the Parris

household in January/February 1692 and end in May 1693 with the last trials,

but some start earlier to place the trials in a wider context of other

witch-hunts, and some end later to include information about restitution.

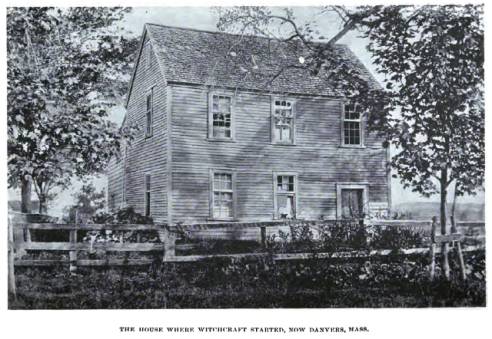

The

preacher’s house in Salem Village where accusations of witchcraft began, as

photographed in the late 19th century

In Salem Village in

1692, Betty Parris, age 9, and her cousin Abigail Williams, age

11, the daughter and niece (respectively) of Reverend Samuel Parris,

began to have fits described as "beyond the power of Epileptic Fits or

natural disease to effect" by John Hale, minister in nearby Beverly.

The girls screamed, threw things about the room, uttered strange sounds,

crawled under furniture, and contorted themselves into peculiar positions. The

girls complained of being pinched and pricked with pins. A doctor,

historically assumed to be William Griggs, could find no physical evidence of

any ailment. Other young women in the village began to exhibit similar

behaviours.

The first three people

accused and arrested for allegedly afflicting Betty Parris, Abigail Williams,

12-year-old Ann Putnam, Jr., and Elizabeth Hubbard were Sarah

Good, Sarah Osborne, and Tituba. Sarah Good was poor and

known to beg for food or shelter from neighbours. Sarah Osborne had married her

servant and rarely attended church meetings. Tituba, as a slave of a different

ethnicity than the Puritans, was an obvious target for accusations. All of

these women fit the description of the "usual suspects" for

witchcraft accusations, and no one stood up for them. These women were

brought before the local magistrates on the complaint of witchcraft and

interrogated for several days.

Other accusations followed in March: Martha Corey,

Dorothy Good and Rebecca Nurse in Salem Village, and Rachel Clinton in

nearby Ipswich. Martha Corey had voiced scepticism about the credibility

of the girls' accusations, drawing attention to herself. The charges against

her and Rebecca Nurse greatly concerned the community because Martha Corey was

a full covenanted member of the Church in Salem Village, as was Rebecca Nurse

in the Church in Salem Town. If such upstanding people could be witches,

then anybody could be a witch, and church membership was no protection from

accusation. Dorothy Good, the daughter of Sarah Good, was only 4 years old,

and when questioned by the magistrates her answers were construed as a

confession, implicating her mother.

In April, the stakes

rose. When Sarah Cloyce (Nurse's sister) and Elizabeth Proctor were

arrested, they were brought before John Hathorne and Jonathan Corwin,

not only in their capacity as local magistrates, but as members of the

Governor's Council, at a meeting in Salem Town. Present for the examination

were Deputy Governor Thomas Danforth, and Assistants Samuel Sewall,

Samuel Appleton, James Russell, and Isaac Addington. Objections by John

Proctor during the proceedings resulted in his arrest that day as well.

Within a week, Giles Corey, Mary Warren (a servant

in the Proctor household and sometime accuser herself), and many others and

were arrested and examined. Mary Warren, along with other women, all confessed

and began naming additional people as accomplices.

Numerous additional arrests followed.

Cotton Mather wrote to

one of the judges, voicing his support of the prosecutions, but cautioning him

of the dangers of relying on spectral evidence (dreams and visions in

which the accuser sees the accused doing evil things) and advising the court on

how to proceed. The Court

convened in Salem Town on June 2, 1692, with William Stoughton, the new

Lieutenant Governor, as Chief Magistrate. Bridget Bishop's case was the

first brought to the grand jury, who endorsed all the indictments against her.

She went to trial the same day and was found guilty. On June 3, the grand jury

endorsed indictments against Rebecca Nurse and John Willard, but it is

not clear why they did not go to trial immediately as well. Bridget Bishop

was executed by hanging on June 10, 1692.

In June, more people

were accused, arrested and examined, but now in Salem Town, by former local

magistrates John Hathorne, Jonathan Corwin, and Bartholomew Gedney who

had become judges. At the end of June and beginning of July, grand juries

endorsed indictments against Sarah Good, Elizabeth Procter, John

Procter, and many others. Among these, Sarah Good and Rebecca Nurse,

went on to trial at this time, where they were found guilty, and executed in

1692. In mid-July as well, the primary source of accusations moved from Salem

Village to Andover, when the constable there asked to have some of the

afflicted girls in Salem Village visit with his wife to try to determine who

caused her afflictions. Elizabeth Procter was given a temporary stay of

execution because she was pregnant. Before being executed, one man named

George Burroughs recited the Lord's Prayer perfectly -- supposedly something

that was impossible for a witch -- but Cotton Mather was present and reminded

the crowd that the man had been convicted before a jury. On August 19, 1692, he

along with others including John Procter was hanged.

In September, grand

juries indicted eighteen more people, including Giles Corey. On

September 19, 1692, Giles Corey refused to plead at arraignment, and was

subjected to peine forte et dure, a form of torture in which the subject

is pressed beneath an increasingly heavy load of stones, in an attempt to make

him enter a plea.

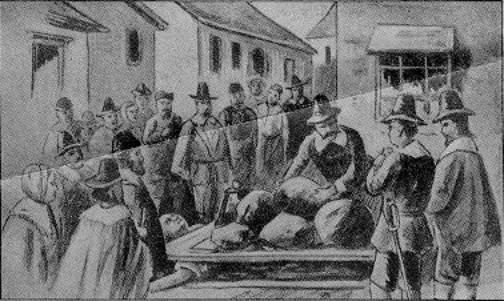

Giles

Corey being “pressed” to death under the weight of stones in order to force a

confession of witchcraft.

After two days of peine fort et dure,

Corey died, his chest crushed, without entering a plea. Though his refusal

to plead is often explained as a way of preventing his possessions from being

confiscated by the state, this is not true; the possessions of convicted

witches were often confiscated, and the possessions of persons accused but not

convicted were confiscated before a trial, as in the case of Corey's neighbour

John Proctor and the wealthy Englishmen of Salem Town. Some historians

hypothesize that Giles Corey's personal character, a stubborn and lawsuit-prone

old man who knew he was going to be convicted regardless, led to his

recalcitrance.

How The Witch Trials were Conducted

After someone concluded

that a loss, illness or death had been caused by witchcraft, the accuser would

enter a complaint against the alleged witch with the local magistrates. If the

complaint was deemed credible, the magistrates would have the person arrested

and brought in for a public examination, essentially an interrogation, where

the magistrates pressed the accused to confess. If the magistrates at this

local level were satisfied that the complaint was well-founded, the prisoner

was handed over to be dealt with by a superior court.

Not even in death were the accused witches granted peace or respect. As convicted witches, Rebecca Nurse and Martha Corey had been excommunicated from their churches and none was given proper burial. As soon as the bodies of the accused were cut down from the trees, they were thrown into a shallow grave and the crowd would disperse. Oral history claims that the families of the dead reclaimed their bodies after dark and buried them in unmarked graves on family property. The record books of the time do not mention the deaths of any of those executed.

The Witch Cake

At some point in

February 1692, likely between the time when the afflictions began but before

specific names were mentioned, a neighbour of Rev. Parris, Mary Sibly

(aunt of the afflicted Mary Walcott), instructed John Indian, one of the minister's

slaves, to make a "witch cake", using traditional English

white magic to discover the identity of the witch who was afflicting the girls.

The cake, made from rye meal and urine from the afflicted girls, was fed to a

dog. According to English folk understanding of how witches accomplished

affliction, when the dog ate the cake, the witch herself would be hurt because

invisible particles she had sent to afflict the girls remained in the girls'

urine, and her cries of pain when the dog ate the cake would identify her as

the witch.

Reverend Parris spoke

with Sibly privately about her "grand error" and accepted her

"sorrowful confession." During his Sunday sermon, he addressed his

congregation about the "calamities" that had begun in his own

household, but stated, "it never brake forth to any considerable light,

until diabolical means were used, by the making of a cake by my Indian man, who

had his direction from this our sister, Mary Sibly", going on to admonish

all against the use of any kind of magic, even white magic, because it was

essentially, "going to the Devil for help against the Devil". Mary

Sibley publicly acknowledged the error of her actions before the congregation,

who voted by a show of hands that they were satisfied with her admission of error.

Tituba

This

19th century representation of "Tituba and the Children," by Alfred

Fredericks, originally appeared in "A Popular History of the United

States", Vol. 2, by William Cullen Bryant (1878)

Traditionally, the "afflicted" girls are

said to have been "entertained" by Parris' slave woman, Tituba,

who supposedly taught them about "voodoo" in the kitchen of

the parsonage during the winter of 1692, although there is no contemporary

evidence to support the story. A variety of secondary sources typically relate

that a "circle" of the girls, with Tituba's help, tried their hands

at fortune telling, using the white of an egg and a "glass" (a

mirror) to create a primitive crystal ball to divine the professions of their

future spouses, and scared one another when one supposedly saw the shape of a

coffin instead. The story is drawn from John Hale's book about the

trials, but in his account, only one of the "afflicted" girls, not a

group of them, had confessed to him afterwards that she had once tried this.

Hale did not mention Tituba as having any part of it, nor when it had occurred.

Tituba's race is often

cited as Carib-Indian or that she was of African descent, but contemporary

sources describe her only as an "Indian".

Research by Elaine Breslaw has suggested that she may well have been captured

in what is now Venezuela and brought to Barbados, and so may have been an

Arawak Indian. Other accounts describe her as a "Spanish Indian".

Contrary to the folklore, there is no evidence to support the assertion that

Tituba told any of the girls any stories about using magic.

The touch test

The most infamous way to

discover witchcraft – and in direct opposition to what Parris had advised his

own parishioners in Salem Village – was the "touch test" used in

Andover during preliminary examinations in September 1692. As several of those

accused later recounted, "we were blindfolded, and our hands were laid

upon the afflicted persons, they being in their fits and falling into their

fits at our coming into their presence, as they said. Some led us and laid our

hands upon them, and then they said they were well and that we were guilty of

afflicting them; whereupon we were all seized, as prisoners, by a warrant from

the justice of the peace and forthwith carried to Salem" Rev.

John Hale explained how this supposedly worked: "the Witch by the cast of

her eye sends forth a Malefick Venome into the Bewitched to cast him into a

fit, and therefore the touch of the hand doth by sympathy cause that venome to

return into the Body of the Witch again".

Response to the Witch Trials in Salem

Soon after, there was

widespread criticism of the witch-hunting in Salem. In the decades following

the trials, the issues primarily had to do with establishing the innocence of

the individuals who were convicted and compensating the survivors and families,

and in the following centuries, the descendants of those unjustly accused and

condemned have sought to honour their memories. Hale’s account of the Trials

was published in 1702 after his death. Expressing regret over the actions

taken, Hale admitted, "Such was the darkness of that day, the tortures and

lamentations of the afflicted, and the power of former presidents, that we

walked in the clouds, and could not see our way". Various petitions were filed

between 1700 and 1703 with the Massachusetts government, demanding that the

convictions be formally reversed. Those tried and found guilty were considered

dead in the eyes of the law, and with convictions still on the books, those not

executed were vulnerable to further accusations. The General Court initially

reversed its judgments only for those who had filed petitions; among those

convicted but not yet executed was Elizabeth Proctor. In 1703, another

petition was filed, requesting a more equitable settlement for those wrongly

accused, but it wasn't until 1709, when the General Court received a further

request, that it took action on this proposal. In May 1709, 22 people who had

been convicted of witchcraft, or whose relatives had been convicted of witchcraft,

began to seek both a reversal of the court’s judgments against them as well as

compensation for their financial losses.

Repentance was evident

within the Salem Village church. In 1703, the church’s decision was finally

reversed concerning the excommunication of Martha Corey. In 1706, when Ann

Putnam, one of the most active accusers, joined the Salem Village

church, she publicly asked forgiveness. She claimed that she had not

acted out of malice, but was being deluded by Satan into denouncing innocent

people, and mentioned Rebecca Nurse in particular, and was accepted for full

membership. Financial compensation was given to the survivors by 1711, and

in 1712, the Salem church reversed Noyes' earlier excommunications of their

former members, Rebecca Nurse and Giles Corey.

The Puritans

A Puritan of 16th

and 17th century England was an associate of any number of disparate religious

groups advocating for more "purity" of worship and doctrine, as well

as personal and group piety. Puritans felt that the English Reformation had not

gone far enough, and that the Church of England was tolerant of practices which

they associated with the church of Rome. The word "Puritan" was

originally an alternate term for "Cathar" and was a pejorative used

to characterize them as extremists similar to the Cathari of France. The

Puritans sometimes cooperated with presbyterians, who put forth a number of

proposals for "further reformation" in order to keep the Church of

England more closely in line with the Reformed Churches on the Continent.

Background

The term

"Puritan" was not coined until the 1560s, when it appears as a term

of abuse for those who proposed radical reforms. Throughout the reign of

Elizabeth I, the Puritan movement involved both a political and a social component.

Politically, the movement attempted, mostly unsuccessfully, to have Parliament

pass legislation to replace episcopacy with presbyterianism, and to alter the

1559 Book of Common Prayer to remove elements considered odious by the

Puritans. Socially, the Puritan movement called for a greater commitment to

Jesus Christ on the part of its members and for greater levels of personal

holiness. By the end of Elizabeth's reign, the Puritans constituted a

distinct social group within the Church of England who regarded themselves as

the godly, and who held out little hope for their neighbours who remained

attached to "popish superstitions" and worldliness. However, most

Puritans were non-Separating Puritans who remained within the Church of

England, and only a small number of Puritans became Separating Puritans

or Separatists who left the Church of England altogether. Although the

Puritan movement was occasionally subjected to suppression by the bishops of

the Church of England, in many places, individual ministers were able to omit

disliked portions of the Book of Common Prayer and to be especially attentive

to the needs of the Puritans.

Congregationalism

The Church of England as

a whole was Calvinist. But the Puritan movement was more strict than Calvinism,

taking on the form of congregationalism. Puritan worship was plain,

resembling a secular lecture with women strictly segregated from men, and tight

control was exercised over the personal habits of members of Puritan

congregations to enforce piety. In 1633, the Church of England moved away from

Puritanism and rigorously enforced the law against ministers who deviated from

the Book of Common Prayer, or who violated the ban on preaching about

predestination. As a result, many Puritans participated in the Great Migration,

founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony as a Puritan haven. The Puritan

movement in England was a major reason for the English Civil War, during which

the Puritans formed the backbone of the parliamentary side.

History

Puritan suspected that King Charles I

of England was secretly planning to restore Roman Catholicism. As such, the

Parliament, heavily influenced by its Puritan members, was reluctant to grant

Charles revenue, since they feared that any revenue granted might be used to

support an army that would re-impose Catholicism on England. For example, when

Charles wanted to intervene in the Thirty Years' War by declaring war on Spain,

Parliament granted him only £140,000, a totally insufficient sum to pursue the

war. Charles was so outraged by Parliament's opposition to his policies that he

determined to rule without ever calling a parliament again, thus initiating the

period known as his Personal Rule (1629-1640), which his enemies termed

the Eleven Years' Tyranny.

The Great Migration and the foundation of Puritan New England, 1630-1642

The events of 1629

convinced many Puritans that King Charles was an ardent foe of further church

reforms. Since King Charles was only 29 years old in 1629, they were thus faced

with the prospect of countless decades without reforms and with their proposals

being suppressed. Given this situation, some Puritans began considering

founding their own colony where they could worship in a fully-reformed church.

One group of separatist Puritans had already settled in New England: the

Pilgrims.

19th-century

painting depicting the Pilgrims landing at Plymouth Rock in 1620.

Many Puritans had grown disillusioned and wanted

to move somewhere where they could retain their English identity, while also

worshipping God in the way they believed was required. As such, the

congregation voted to found a colony. The group ultimately decided to move to

New England. In 1620, the Pilgrims left for New England onboard the Mayflower,

landing at Plymouth Rock. The colony founded by the Pilgrims was called Plymouth

Colony.

John Winthrop,

a Puritan lawyer, began to explore the idea of creating a Puritan colony in New

England. After all, the Pilgrims at Plymouth Colony had proven that such a

colony was viable.

Winthrop sailed for New England in 1630 along with

700 colonists on board eleven ships known collectively as the Winthrop Fleet.

The move of the Puritans from England to the New England colonies along the

Northeast of what would one day be the United States is called “the Great

Migration.”

Most of the Puritans who emigrated settled in the New England area. However, the Great Migration of Puritans was relatively short-lived and not as large as is often believed. It began in earnest in 1629 with the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and ended in 1642 with the start of the English Civil War when King Charles I effectively shut off emigration to the colonies, and when Puritans felt less menaced by Royalist decree. From 1629 through 1643 approximately 21,000 Puritans emigrated to New England. This is actually far less than the number of British subjects who emigrated to Ireland, Canada, and the Caribbean during this time.

The Great Migration of

Puritans to New England was primarily an exodus of families. Between 1630 and

1640 over 13,000 men, women, and children sailed to Massachusetts. The

religious and political factors behind the Great Migration influenced the

demographics of the emigrants. Rather than groups of young men seeking

economic success, Puritan ships were laden with “ordinary” people, old and

young, families as well as individuals. Just a quarter of the emigrants were in

their twenties when they boarded ship in the 1630s, making young adults not

predominant in New England settlements. The New World Puritan population

can be seen as more of a cross section in age of English population than those

of other colonies. There was little intermarriage with natives. The women who

emigrated were critical agents in the success of the establishment and

maintenance of the Puritan colonies in North America. Success in the early

colonial economy depended largely on labour, which was conducted by members of

Puritan families. It was through this labour that Puritans endeavoured to

create their “city on a hill”, a productive, morally exemplary colony far from

the corruption of the Church of England.

New England theological controversies, 1632-1642

As noted earlier, the

vast majority of Puritans who settled in the Massachusetts Bay Colony were

non-separating Puritans. This meant that, while they disliked many of the

practices of the Church of England, they refused to separate from the Church of

England. This position led to squabbles with Separating Puritans.

Roger Williams,

a Separating Puritan minister, attempted to become pastor of the church at

Salem, but was blocked by Boston political leaders, who objected to his

separatism. He thus spent two years with his fellow Separatists in the Plymouth

Colony, but ultimately came into conflict with them and returned to Salem.

There, he became pastor in May 1635, against the objection of the Boston

authorities. Williams set forth a manifesto in which he declared that 1) the

Church of England was apostate and fellowship with it was a grievous sin; 2)

the Massachusetts Colony's charter falsely said that King Charles was a

Christian; 3) that the colony should not be allowed to impose oaths on its

citizens.

Williams' actions so

outraged the Puritan leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony that they expelled

him from the colony. In 1636, he founded the city of Providence, Rhode Island. Williams

was one of the first Puritans to advocate separation of church and state and

Rhode Island was one of the first places in the Christian world to recognize

freedom of religion.

Another

controversy erupted

around Anne Hutchinson. She and her family moved to

the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1634, following their Puritan minister John

Cotton. Following Cotton, Hutchinson took up the idea of double

predestination, which held that God chose those who would go to heaven

(the elect) and those who would go to hell (the reprobate), and that His

decision inevitably and infallibly came to pass. Applying Cotton’s ideas,

Hutchinson argued that people were either relying on good works for their

salvation, and therefore were really damned (because human beings cannot save

themselves), or else they were relying upon God’s grace or His love, and were

therefore really saved).

Nineteenth-century

painting depicting Anne Hutchinson's (1591-1643) trial before the Massachusetts

General Court in 1637, which led to her banishment from the Massachusetts Bay

Colony.

By 1637, Hutchinson's teachings had grown

controversial within the colony for a number of reasons. First, some Puritans

objected to a woman occupying such a prominent role as a teacher in the church.

Second, Hutchinson began denouncing various Puritan ministers in the colony and

sometimes spoke as if John Cotton were the only minister in the entire colony

who was preaching correctly. Thirdly, some of Hutchinson's views were

heretical; she seemed to preach that “the elect” or the special “in-group”

among them did not have to follow the laws of God or morality.

Hutchinson was called

before the court to explain herself. She told them that God had spoken to her

and told her the future and what she should preach. The Puritans generally

believed that God communicated with individuals only through scripture. As

such, the court decided to banish her from the colony. As a result, in 1638,

Hutchinson and several of her followers left the Massachusetts Bay Colony and

founded Portsmouth, Rhode Island.

Puritan Religion

The central tenet of

Puritanism was God's supreme authority over human affairs, particularly in the

church, and especially as expressed in the Bible. This view led them to seek

both individual and group conformity to the teaching of the Bible, and it led

them to pursue both moral purity down to the smallest detail as well as church

purity to the highest level.

The words of the Bible

were the origin of many Puritan cultural ideals, especially regarding the roles

of men and women in the community. While both sexes carried the stain of

original sin, for a girl, original sin suggested more than the roster of

Puritan character flaws. Eve’s corruption, in Puritan eyes, extended to all

women, and justified marginalizing them within churches' hierarchical

structures. Women were therefore treated as the spiritual inferiors of men. An

example is the different ways that men and women were made to express their

conversion experiences. For full membership, the Puritan church insisted not

only that its congregants lead godly lives and exhibit a clear understanding of

the main tenets of their Christian faith, but they also must demonstrate that

they had experienced true evidence of the workings of God’s grace in their

souls. Only those who gave a convincing account of such a conversion could be

admitted to full church membership. Women were not permitted to speak in

church after 1636 (although they were allowed to engage in religious

discussions outside of it, in various women-only meetings), and thus could not

narrate their conversions.

On the individual level, the Puritans emphasized that each person should be continually reformed by the grace of God to fight against indwelling sin and do what is right before God. A humble and obedient life would arise for every Christian. Puritan culture emphasized the need for self-examination and the strict accounting for one’s feelings as well as one’s deeds. This was the a very important aspect of their daily experience, which women in turn placed at the heart of their work to sustain family life.

Puritans rejected seeing

or staging plays or dramas and other worldly enjoyments. The Pilgrims (the

separatist, congregationalist Puritans who went to North America) are likewise

famous for banning from their New England colonies many secular entertainments,

such as games of chance, maypoles, and drama, all of which were perceived as

kinds of immorality.

At the level of the church community, the Puritans believed that worship in the church ought to be strictly regulated by what is commanded in the Bible. The Puritans condemned as idolatry many worship practices regardless of the practices' antiquity or widespread adoption among Christians, which their opponents defended with tradition. Puritans only accepted a minimal amount of ritual and decoration in their worship, but they put lots of emphasis on preaching. They eliminated the use of musical instruments in their worship services, but outside of church, they were quite fond of music and encouraged it in certain ways.

Another important

distinction was the Puritan approach to church-state relations. They opposed

the Anglican idea of the supremacy of the monarch in the church,

and, following Calvin, they argued that the only head of the Church in

heaven or earth is Christ (not the Pope or the monarch). However, they believed

that secular governors are accountable to God (not through the church, but

alongside it) to protect and reward virtue, including "true

religion", and to punish wrongdoers — a policy that is best described as

non-interference rather than separation of church and state. The separating

Congregationalists, a segment of the Puritan movement more radical than the

Anglican Puritans, believed the Divine Right of Kings was heresy, a

belief that became more pronounced during the reign of Charles I of England.

Other notable beliefs include:

š

An emphasis on private study of the Bible

š

A desire to see education and enlightenment for

the masses (especially so they could read the Bible for themselves)

š

The priesthood of all believers

š

Simplicity in worship, the exclusion of vestments,

images, candles, etc.

š

Did not celebrate traditional holidays that they

believed to be in violation of the regulative principle of worship.

š

Believed the Sabbath was still obligatory for

Christians, although they believed the Sabbath had been changed to Sunday

In modern usage, the word puritan is often

used in the negative sense for someone who has strict views on sexual morality,

disapproves of recreation, and wishes to impose these beliefs on others. This

popular image is not very accurate as a description of Puritans in England, but

it applies better as a description of Puritans in colonial America, who were

among the most radical Puritans and whose social experiment took the form of a theocracy.

The Puritan spirit in the United States

Some have suggested that

it is a "Puritan spirit" in the United States' political culture that

creates a tendency to oppose things such as alcohol and open sexuality. However,

the Puritans were not opposed to drinking alcohol in moderation or to enjoying

their sexuality within the bounds of marriage as a gift from God. In fact,

spouses (albeit, in practice, mainly females) were disciplined if they did not

perform their sexual marital duties. Because of these beliefs, the Puritans did

publicly punish drunkenness and sexual relations outside of marriage.

Alexis de Tocqueville

suggested in Democracy in America that the Pilgrims' Puritanism was the

very thing that provided a firm foundation for American democracy, and in his

view, these Puritans were hard-working, egalitarian, and studious. The theme of

a religious basis of economic discipline is echoed in sociologist Max Weber's

work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.

McCarthyism

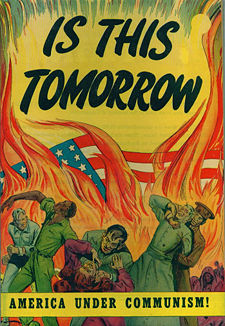

A

1947 comic book published by the Catechetical Guild Educational Society warning

of the supposed dangers of a Communist takeover.

McCarthyism

is a term describing the intense anti-communist suspicion in the United

States in a period that lasted roughly from the late 1940s to the late 1950s.

This period is also referred to as the Second Red Scare, and coincided

with increased fears about communist influence on American institutions and

espionage by Soviet agents. Originally coined to criticize the actions of U.S.

Senator Joseph McCarthy, "McCarthyism" later took on a more

general meaning, not necessarily referring to the conduct of Joseph McCarthy

alone.

During this time many

thousands of Americans were accused of being Communists or communist

sympathizers and became the subject of aggressive investigations and

questioning before government or private-industry panels, committees and

agencies. The primary targets of such suspicions were

government employees, those in the entertainment industry, educators and union

activists. Suspicions were often given credence despite inconclusive or

questionable evidence, and the level of threat posed by a person's real or

supposed leftist associations or beliefs was often greatly exaggerated. Many

people suffered loss of employment, destruction of their careers, and even

imprisonment. Most of these punishments came about through trial verdicts

later overturned, laws that would be declared unconstitutional, dismissals

for reasons later declared illegal or actionable, or extra-legal

procedures that would come into general disrepute.

The most famous examples

of McCarthyism include the Hollywood blacklist and the investigations

and hearings conducted by Joseph McCarthy. It was a widespread social and

cultural phenomenon that affected all levels of society and was the source of a

great deal of debate and conflict in the United States.

Origins of McCarthyism

Herbert

Block (aka 'Herblock') coined the term "McCarthyism" in this cartoon

in the March 29, 1950 Washington Post

The historical period

that came to be known as McCarthyism began well before Joseph McCarthy's own involvement

in it. There are many factors that can be counted as contributing to

McCarthyism, some of them extending back to the years of the First Red Scare

(1917-1920), and indeed to the inception of Communism as a recognized political

force. Thanks in part to its success in organizing labor unions and its early

opposition to fascism, the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA)

increased its membership through the 1930s, reaching a peak of 50,000 members

in 1942.

While the United States was engaged in World War II and allied with the Soviet Union, the issue of anti-communism was largely muted. With the end of World War II, the Cold War began almost immediately, as the Soviet Union installed repressive Communist puppet régimes across Central and Eastern Europe.

Events in 1949 and 1950

sharply increased the sense of threat from Communism in the United States. The

Soviet Union tested an atomic bomb in 1949, earlier than many analysts had

expected. That same year, Mao Zedong's Communist army gained control of

mainland China despite heavy financial support of the opposing Kuomintang by

the U.S. In 1950, the Korean War began, pitting U.S., U.N. and South Korean

forces against Communists from North Korea and China. Julius and Ethel

Rosenberg were arrested in 1950 on charges of stealing atomic bomb secrets for

the Soviets and were executed in 1953.

There were also more

subtle forces encouraging the rise of McCarthyism. It had long been a practice

of more conservative politicians to refer to liberal reforms such as

child labor laws and women's suffrage as "Communist" or "Red

plots." This tendency increased in reaction to the New Deal policies

of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Many conservatives equated the New Deal

with socialism or Communism, and saw its policies as evidence that the

government had been heavily influenced by Communist policy-makers in the

Roosevelt administration. In general, the vaguely defined danger of

"Communist influence" was a more common theme in the rhetoric of

anti-Communist politicians than was espionage or any other specific activity.

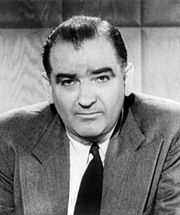

Senator

Joseph McCarthy

Joseph McCarthy's

involvement with the ongoing cultural phenomenon that would bear his name began

with a speech he made. He produced a piece of paper that he claimed contained a

list of known Communists working for the State Department. McCarthy is usually

quoted as saying: "I have here in my hand a list of 205 — a list of names

that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the

Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping policy in

the State Department." This speech resulted in a flood of press attention

to McCarthy and set him on the path that would characterize the rest of his

career and life.

The first recorded use

of the term McCarthyism was in a political cartoon by Washington Post

editorial cartoonist Herbert Block. The cartoon depicted

four leading Republicans trying to push an elephant (the traditional symbol of

the Republican Party) to stand on a teetering stack of ten tar buckets, the

topmost of which was labelled "McCarthyism."

The institutions of McCarthyism

There were many anti-Communist committees, panels

and "loyalty review boards" in federal, state and local governments,

as well as many private agencies that carried out investigations for small and

large companies concerned about possible Communists in their work force. In Congress, the most notable bodies for

investigating Communist activities were the House Un-American Activities

Committee (HUAC), the Senate Internal Security

Subcommittee and the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. Between

1949 and 1954, a total of 109 investigations were carried out by these and

other committees of Congress.

Loyalty-security

reviews

In the federal

government, President Harry Truman initiated a program of loyalty

reviews for government employees in 1947. Truman's mandate called for dismissal

if there were "reasonable grounds... for belief that the person involved

is disloyal to the Government of the United States." Truman, a Democrat,

was probably reacting in part to the Republican sweep in the 1946 Congressional

election, and felt a need to counter the growing criticism from conservatives

and anti-communists.

When President Dwight

Eisenhower took office in 1953, he strengthened and extended Truman's

loyalty review program, while decreasing the avenues of appeal available to

dismissed employees. Hiram Bingham, Chairman of the Civil Service Commission

Loyalty Review Board, referred to the new rules he was obliged to enforce as

"just not the American way of doing things." Similar loyalty

reviews were established in many state and local government offices and some

private industries across the nation. In 1958 it was estimated that roughly one

out of every five employees in the United States was required to pass some sort

of loyalty review.

Once a person lost a job due to an unfavourable

loyalty review, it could be very difficult to find other employment.

"A man is ruined everywhere and forever," in the words of the

chairman of President Truman's Loyalty Review Board. "No responsible

employer would be likely to take a chance in giving him a job."

The Department of

Justice started keeping a list of organizations that it deemed subversive

beginning in 1942. This list was first made public in 1948,

when it included 78 items. At its longest, it comprised 154 organizations, 110

of them identified as Communist. In the context of a loyalty review, membership

in a listed organization was meant to raise a question, but not to be

considered proof of disloyalty. One of the most common causes of suspicion was

membership in the Washington Bookshop Association, a left-leaning organization

that offered lectures on literature, classical music concerts and discounts on

books.

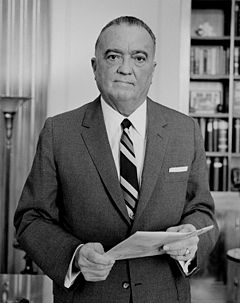

J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI

J.

Edgar Hoover in 1961

The FBI have been called "the single

most important component of the anti-communist crusade." FBI director J.

Edgar Hoover was one of the nation's most fervent anti-communists, and one

of the most powerful. Hoover designed President Truman's loyalty-security

program, and its background investigations of employees were carried out by FBI

agents. This was a major assignment that led to the number of agents in the

Bureau being increased from 3,559 in 1946 to 7,029 in 1952. Hoover's extreme

sense of the Communist threat and the politically conservative standards of

evidence applied by his bureau resulted in thousands of government workers

losing their jobs. Due to Hoover's insistence upon keeping the identity of his

informers secret, most subjects of loyalty-security reviews were not allowed to

cross-examine or know the identities of those who accused them. In many cases

they were not even told what they were accused of.

Hoover's influence

extended beyond federal government employees and beyond the loyalty-security

programs. The records of loyalty review hearings and investigations were

supposed to be confidential, but Hoover routinely gave evidence from them to

congressional committees such as HUAC. From 1951 to 1955, the FBI

operated a secret "Responsibilities Program" that distributed

anonymous documents with evidence from FBI files of Communist affiliations on

the part of teachers, lawyers, and others. Many people accused in these

"blind memoranda" were fired without any further process. The

FBI engaged in a number of illegal practices in its pursuit of information on

Communists, including burglaries, opening mail and illegal wiretaps.

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC)

The House Un-American

Activities Committee (HUAC) was the most prominent and active government

committee involved in anti-Communist investigations.

Formed in 1938, HUAC investigated a variety of "activities,"

including those of German-American Nazis during World War II. The Committee

soon focused on Communism. HUAC achieved its greatest fame and notoriety with

its investigation into the Hollywood film industry. It was during these

investigative hearings that what became known as the "$64 question"

was asked: "Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist

Party of the United States?" Anyone who refused to answer the

Committee’s questions on the grounds that the constitution protected their free

speech and freedom of assembly was sentenced to prison for contempt of

Congress. In the future, witnesses who were determined not to cooperate with

the Committee would claim their Fifth Amendment protection against

self-incrimination. While this usually protected them from a contempt of

Congress citation, it was considered grounds for dismissal by many government

and private industry employers. The legal requirements for Fifth Amendment

protection were such that a person could not testify about his own association

with the Communist Party and then refuse to "name names" of

colleagues with Communist affiliations. Thus many faced a choice between

"crawl[ing] through the mud to be an informer," or becoming known as

a "Fifth Amendment Communist,"—an epithet often used by

Senator McCarthy.

Blacklists

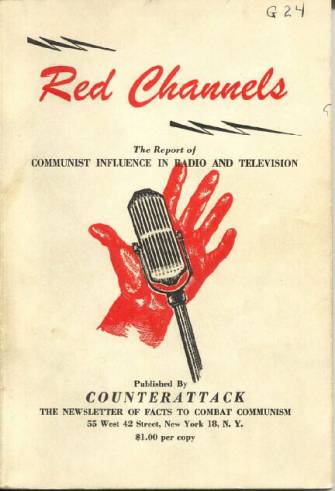

Red

Channels, a 1950 publication claiming to document

"Communist influence in radio and television"

In 1947, the Motion

Picture Association of America made a public statement that it would not hire

anyone who was a known communist. This open capitulation to the attitudes of

McCarthyism marked the beginning of the Hollywood blacklist. In spite of

the fact that hundreds would be denied employment, the studios, producers and

other employers did not publicly admit that a blacklist existed. Books such as Red

Channels were published to keep track of communist and leftist

organizations and individuals.

Laws and arrests

There were several

attempts to introduce legislation or apply existing laws to help to protect the

United States from the perceived threat of Communist subversion. The Alien

Registration Act or Smith Act of 1940 made it a criminal offence for

anyone to "knowingly or wilfully advocate, abet, advise or teach the […]

desirability or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States

or of any State by force or violence, or for anyone to organize any association

which teaches, advises or encourages such an overthrow, or for anyone to become

a member of or to affiliate with any such association". Hundreds of

Communists and others were prosecuted under this law between 1941 and 1957.

Popular support for McCarthyism

Flier

issued in May 1955 by the Keep America Committee urging readers to "fight

communistic world government" by opposing public health programs

McCarthyism was

supported by a variety of groups, including the American Legion, Christian

fundamentalists and various other anti-communist organizations.

One core element of support was a variety of militantly anti-communist women's

groups such as the American Public Relations Forum and the Minute Women of the

U.S.A.. These organized tens of thousands of housewives into study groups,

letter-writing networks, and patriotic clubs that coordinated efforts to

identify and eradicate subversion.

Although far-right

radicals were the bedrock of support for McCarthyism, they were not alone. A

broad "coalition of the aggrieved" found McCarthyism attractive, or

at least politically useful. Common themes uniting the coalition were

opposition to internationalism, particularly the United Nations; opposition to

social welfare provisions, particularly the various programs established by the

New Deal; and opposition to efforts to reduce inequalities in the social

structure of the United States.

One focus of popular

McCarthyism concerned the provision of public health services, particularly vaccination,

mental health care services and fluoridation, all of which were

deemed by some to be communist plots to poison or brainwash the American

people. Many ordinary Americans became convinced that there must be

"no smoke without fire" and lent their support to McCarthyism. In

January 1954, a Gallup poll found that 50% of the American public supported

McCarthy, while only 29% had an unfavourable opinion of the senator. Earl

Warren, the Chief Justice of the United States, commented that if the United

States Bill of Rights had been put to a vote it probably would have been

defeated.

Victims of McCarthyism

It is difficult to

estimate the number of victims of McCarthyism. The number imprisoned is in the

hundreds, and some ten or twelve thousand lost their jobs.

In many cases, simply being asked to appear before the HUAC or one of the other

committees was sufficient cause to be fired. Many of those who were imprisoned,

lost their jobs or were questioned by committees did in fact have a past or

present connection of some kind with the Communist Party. But for the vast

majority, both the potential for them to do harm to the nation and the nature

of their communist affiliation were tenuous. Suspected homosexuality was

also a common cause for being targeted by McCarthyism. According to some

scholars, this resulted in more persecutions than did alleged connection with

Communism.

In the film industry,

over 300 actors, authors and directors were denied work in the U.S. through the

unofficial Hollywood blacklist. Blacklists were at work throughout the

entertainment industry, in universities and schools at all levels, in the legal

profession, and in many other fields. A port security program initiated by the

Coast Guard shortly after the start of the Korean War required a review of

every maritime worker who loaded or worked aboard any American ship, regardless

of cargo or destination. As with other loyalty-security reviews of McCarthyism,

the identities of any accusers and even the nature of any accusations were

typically kept secret from the accused. Nearly 3,000 seamen and longshoremen

lost their jobs due to this program alone.

Critical reactions

The 1952 Arthur Miller

play The Crucible used the Salem witch trials as a metaphor for

McCarthyism, suggesting that the process of McCarthyism-style persecution can

occur at any time or place. The play focused heavily on the fact that once

accused, a person would have little chance of exoneration, given the irrational

and circular reasoning of both the courts and the public. Miller would later

write: "The more I read into the Salem panic, the more it touched off

corresponding images of common experiences in the fifties."

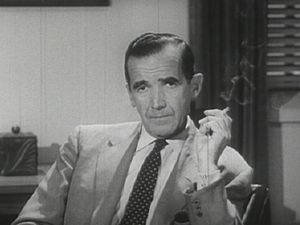

News

analyst Edward R. Murrow

One of the most influential opponents of

McCarthyism was the famed CBS newscaster and analyst Edward R. Murrow.

On October 20, 1953, Murrow's show See It Now aired an episode about the

dismissal of Milo Radulovich, a former reserve Air Force lieutenant who was

accused of associating with Communists. The show was strongly critical of the

Air Force's methods, which included presenting evidence in a sealed envelope

that Radulovich and his attorney were not allowed to open. On March 9, 1954, See

It Now aired another episode on the issue of McCarthyism, this one

attacking Joseph McCarthy himself. Titled "A Report on Senator Joseph R.

McCarthy," it used footage of McCarthy speeches to portray him as

dishonest, reckless and abusive toward witnesses and prominent Americans. In

his concluding comment, Murrow said:

|

“ |

We

must not confuse dissent with disloyalty. We must remember always that

accusation is not proof and that conviction depends upon evidence and due

process of law. We will not walk in fear, one of another. We will not be

driven by fear into an age of unreason, if we dig deep in our history and our

doctrine, and remember that we are not descended from fearful men. |

” |

This broadcast has been cited as a key episode in

bringing about the end of McCarthyism. As the nation moved

into the mid and late fifties, the attitudes and institutions of McCarthyism

slowly weakened. Changing public sentiments undoubtedly had a lot to do with

this, but one way to chart the decline of McCarthyism is through a series of

court decisions.

Though McCarthyism might

seem to be of interest only as a historical subject, the political divisions it

created in the United States continue to make themselves manifest, and the

politics and history of anti-Communism in the United States are still

contentious. One source of controversy is the comparison that a number of

observers have made between the oppression of liberals and leftists during the

McCarthy period and recent actions against Muslims and suspected terrorists.

In The Age of Anxiety: McCarthyism to Terrorism, author Haynes Johnson

compares the "abuses suffered by aliens thrown into high security U.S.

prisons in the wake of 9/11" to the excesses of the McCarthy era.

Similarly, David D. Cole has written that the Patriot Act "in effect

resurrects the philosophy of McCarthyism, simply substituting 'terrorist' for

'communist.'"