Antisemitism

A badge that all the Jews in Europe were forced to

wear under Hitler

Antisemitism is discrimination, hostility or prejudice directed at Jewish persons as

a religious, racial, or ethnic group. Instances of antisemitism range from

individual hatred to institutionalized, violent persecution. Extreme instances

of persecution include the Spanish Inquisition, eviction from Spain, various

pogroms, and, above all, Adolf Hitler's Holocaust.

Antisemitism can be broadly categorized into three forms:

·

Religious antisemitism, also known as anti-Judaism,

focuses on the practice of Judaism itself. Discrimination against Jews has been

commonplace in Christian and Muslim lands. Sometimes this discrimination is

similar to that suffered by "infidels" in general. At other times,

Jews have been singled out for discrimination. Both Christianity and Islam seek

converts, and Jews that converted (or pretended to, see Marranos) could

escape at least some religious persecution.

·

Racial antisemitism. Racial antisemitism is the

concept that the Jews are a distinct and inferior race. In the late 19th and

early 20th centuries, it gained mainsteam acceptance as part of the eugenics

movement, which categorized non-whites as inferior. It more specifically claims

the so-called Nordic Europeans as superior. Racial antisemites emphasize the

Jews' "alien" extra-European origins. Today, racial antisemitism has

lost general credibility and appears most often among Neo-Nazi and white

supremacist movements.

- New antisemitism is the concept of a new form of 21st century antisemitism coming

simultaneously from the left, the far right, and radical Islam, which

tends to focus on opposition to Zionism and a Jewish homeland in the State

of Israel, and which may deploy traditional antisemitism motifs. The

concept has been criticized for what some authors see as a confusion of

antisemitism and anti-Zionism.

Etymology and usage

The term

Semite refers broadly to speakers of a language group which includes

both Arabs and Jews. However, the term antisemitism

is specifically used in reference to attitudes held towards Jews.

|

Cover page of Marr's The

Way to Victory of Germanicism over Judaism, 1880 edition |

Antisemitic caricature

(France, 1898) |

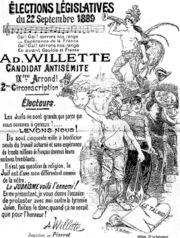

France, 1889. Elections

poster for self-described "candidat antisémite" Adolphe Willette |

Before the extent of the Nazi genocide became widely

known and the term "antisemitism" acquired emotional connotations, it

was not uncommon for a person to self-identify as an antisemite. In the

aftermath of Kristallnacht, Goebbels announced: "The German people is

anti-Semitic. It has no desire to have its rights restricted or to be provoked

in the future by parasites of the Jewish race."

Earliest Antisemitism

The earliest occurrence of antisemitism has

been the subject of debate among scholars. Professor Peter Schafer of the

Freie University of Berlin has argued that antisemitism was first spread by

"the Greek retelling of ancient

Egyptian prejudices". In view of the anti-Jewish writings of the

Egyptian priest Manetho, Schafer suggests that antisemitism may have emerged "in Egypt alone".

Father

Edward H. Flannery, in The Anguish of the Jews: Twenty-Three Centuries of

Antisemitism, traces what he calls the first clear examples of anti-Jewish

sentiment, which he calls "antisemitism," to third century BCE Alexandria.

Hecataetus of Abdera, a Greek historian, wrote that Moses "in remembrance of the exile of his people, instituted for

them a misanthropic and inhospitable way of life." Manetho, an

Egyptian priest and historian, wrote that the Jews were expelled Egyptian lepers who had been taught by Moses

"not to adore the gods." The same themes appeared in the works of

Chaeremon, Lysimachus, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon, and in Apion and Tacitus,

according to Flannery. Agatharchides of Cnidus wrote about the "ridiculous practises" of the Jews and of the

"absurdity of their Law," making a mocking reference to how

Ptolemy Lagus was able to invade Jerusalem in 320 BCE because its inhabitants

were observing the Sabbath.

The

hostility commonly faced by Jews in the Diaspora has been extensively described

by John M. G. Barclay of the University of Durham. The ancient Jewish

philosopher Philo of Alexandria

described an attack on Jews in Alexandria in 38 CE in Flaccus, in which thousands of Jews died. In the analysis of

Pieter W. Van Der Horst, the cause of the violence in Alexandria was that Jews had been portrayed as misanthropes.

Gideon Bohak has argued that early animosity against Jews was not anti-Judaism

unless it arose from attitudes held against Jews alone. Using this stricter

definition, Bohak says that many Greeks

had animosity toward any group they regarded as barbarians. There are other

examples of ancient animosity towards Jews that are not considered by all to

fall within the definition of antisemitism.

Religious antisemitism

Jews have lived as a religious minority in

Christian and Muslim lands since the Roman Empire became Christian.

Christianity and Islam have both portrayed Jews as those who rejected God's

truth. Christians and Muslims have, over the centuries, alternately lived in

peace with Jews and persecuted them.

Antisemitism and the Christian world

Anti-Judaism

in the New Testament

The New

Testament is a collection of religious books and letters written by various

authors. These writings, together with the Old Testament are the foundation

documents of the Christian faith. Most of this collection was written by the

end of the first century. The majority of the New Testament was written by Jews

who became followers of Jesus, and all but two books (Luke and Acts) are

traditionally attributed to such Jewish followers. Nevertheless, there are a

number of passages in the New Testament that some see as antisemitic, or have

been used for antisemitic purposes, most notably:

Jesus speaking to a group of Pharisees: "I know that

you are descendants of Abraham; yet you seek to kill me, because my word finds

no place in you. I speak of what I have seen with my Father, and you do what

you have heard from your father. They answered him, "Abraham is our father."

Jesus said to them, "If you were Abraham's children, you would do what

Abraham did. ... You are of your father the devil, and your will is to do your

father's desires. He was a murderer from the beginning, and has nothing to do

with the truth, because there is no truth in him. When he lies, he speaks

according to his own nature, for he is a liar and the father of lies. But,

because I tell the truth, you do not believe me. Which of you convicts me of

sin? If I tell the truth, why do you not believe me? He who is of God hears the

words of God; the reason why you do not hear them is you are not of God." (John 8:37-39, John 8:44-47)

Stephen speaking before a synagogue council just before

his execution:

"You stiff-necked people, uncircumcised in heart and

ears, you always resist the Holy Spirit. As your fathers did, so do you. Which

of the prophets did not your fathers persecute? And they killed those who

announced beforehand the coming of the Righteous One, whom you have now

betrayed and murdered, you who received the law as delivered by angels and did

not keep it." (Acts 7:51-53, RSV)

"Behold, I will make those of the synagogue of Satan

who say that they are Jews and are not, but lie — behold, I will make them come

and bow down before your feet, and learn that I have loved you." (Revelation 3:9, RSV).

Some biblical scholars point out that Jesus and Stephen

are presented as Jews speaking to other Jews, and that their use of broad

accusation against Israel is borrowed from Moses and the later Jewish prophets

(e.g. Deuteronomy 9:12-14; Deuteronomy 31:27-29; Deuteronomy 32:5, Deuteronomy

32:20-21; 2 Kings 17:13-14; Isiah 1:4; Deuteronomy 9:12-14; Hosea q:12-149;

Hosea 10:9). Jesus once calls his own disciple Peter 'Satan' (Mark 8:33). Other

scholars hold that verses like these reflect the Jewish-Christian tensions that

were emerging in the late first or early second century, and do not originate

with Jesus.

Drawing from the Jewish prophet Jeremiah

(Jeremiah 31:31-34), the New Testament taught that with the death of Jesus a

new covenant was established which rendered obsolete and in many respects

superseded the first covenant established by Moses (Hebrews 8:7-13; Luke

22:20). Observance of the earlier covenant traditionally characterizes Judaism.

This New Testament teaching, and later variations to it, are part of what is

called supersessionism. However, the early Jewish followers of Jesus continued

to practice circumcision and observe dietary laws, which is why the failure to

observe these laws by the first Gentile Christians became a matter of

controversy and dispute some years after Jesus' death (Acts 11:3; Acts 15:1;

Acts 16:3).

The New Testament holds that Jesus'

(Jewish) disciple Judas Iscariot (Mark 14:43-46), the Roman governor Pontius

Pilate along with Roman forces (John 19:11; Acts 4:27) and Jewish leaders and

people of Jerusalem were (to varying degrees) responsible for the death of

Jesus (Acts 13:27) Diaspora Jews are not blamed for events which were

clearly outside their control.

After Jesus' death, the New Testament

portrays the Jewish religious authorities in Jerusalem as hostile to Jesus'

followers, and as occasionally using force against them. Stephen is executed by

stoning (Acts 7:58). Before his conversion, Saul puts followers of Jesus in

prison (Acts 8:3; Galatians 1:13-14; 1 Timothy 1:13). After his conversion,

Saul is whipped at various times by Jewish authorities (2 Corinthians 11:24),

and is accused by Jewish authorities before Roman courts (e.g., Acts 25:6-7).

However, opposition from Gentiles is also cited repeatedly (2 Corinthians

11:26; Acts 16:19; Acts 19:23). More generally, there are widespread references

in the New Testament to suffering experienced by Jesus' followers at the hands

of others (Romans 8:35; 1 Corinthians 4:11; Galatians 3:4; 2 Thessalonians 1:5;

Hebrews 10:32; 1 Peter 4:16; Revelation 20:4).

Passion plays

Passion plays, dramatic stagings

representing the trial and death of Jesus, have historically been used in

remembrance of Jesus' death during Lent. These plays historically blamed the Jews for the death of Jesus in a

polemical fashion, depicting a crowd of Jewish people condemning Jesus to

crucifixion and a Jewish leader assuming eternal collective guilt for the crowd

for the murder of Jesus, which, The Boston Globe explains, "for centuries prompted vicious attacks — or

pogroms — on Europe's Jewish communities".Time magazine in its

article, The Problem With Passion, explains that "such passages

(are) highly subject to interpretation". Although modern

scholars interpret the "blood on

our children" (Matthew 27:25) as "a specific group's oath of responsibility" some audiences have

historically interpreted it as "an

assumption of eternal, racial guilt". This last interpretation has

often incited violence against Jews; according to the Anti-Defamation League,

"Passion plays historically

unleashed the torrents of hatred aimed at the Jews, who always were depicted as

being in partnership with the devil and the reason for Jesus' death".

The Christian Science Monitor, in its article, Capturing the

Passion, explains that "historically, productions have reflected

negative images of Jews and the long-time church teaching that the Jewish

people were collectively responsible for Jesus' death. Violence against Jews as 'Christ-killers' often flared in their

wake." Christianity Today in Why some Jews fear The Passion (of

the Christ) observed that "Outbreaks

of Christian antisemitism related to the Passion narrative have been...numerous

and destructive." The Religion Newswriters Association observed that

"in Easter 2001, three incidents made national

headlines and renewed their fears. One was a column by Paul Weyrich, a

conservative Christian leader and head of the Free Congress Foundation, who

argued that "Christ was crucified by the Jews." Another was sparked

by comments from the NBA point guard and born-again Christian Charlie Ward, who

said in an interview that Jews were persecuting Christians and that Jews

"had his [Jesus'] blood on their hands." Finally, the evangelical

Christian comic strip artist Johnny Hart published a B.C. strip that showed a

menorah disintegrating until it became a cross, with each panel featuring the

last words of Jesus, including "Father, forgive them, for they know not

what they do."

In 1988,

the Bishops' Committee for Ecumenical and Inter religious Affairs of the United

States Conference of Catholic Bishops published Criteria for the Evaluation

of Dramatizations of the Passion, in order to ensure that Passion Plays

adhere to the teaching of the Second Vatican Council and the Pontifical

Biblical Commission as expressed in Nostra Aetate no. 4 (October 28,

1965). These criteria were summarized for the Archdiocese of Boston as:

·

The overriding preoccupation of any

dramatization of the Passion must be, in the words of Ellis Rivkin, not who

killed Christ, but what killed Christ, namely, our sins.

·

Those scripting a Passion play must use

the best available biblical scholarship to elucidate the gospel texts which

were not written to preserve historical facts so much as to proclaim the saving

truth about Jesus.

·

Harmonizing the four accounts of Jesus’

Passion — i.e. constructing a single story of the Passion by combining

elements from the four gospel versions — risks violating the integrity of the

texts, each of which offers a distinct theological interpretation of Jesus ’

death.

·

Because of the nature of the gospels, the

choice of what gospel passages to use in the making of a Passion play must be

guided by the Church’s teaching that “the Jews should not be presented as

rejected or accursed by God as if this followed from Sacred Scripture” (Nostra

Aetate 4). The claim that a passage is “in the Bible” does not suffice to

justify its inclusion.

·

As ignorance of Judaism often leads to

misinterpretation of events, the complexity of the Jewish world of Jesus must

be carefully researched and correctly represented; e.g., it is important

to know that the high priest was appointed by the Roman procurator.

·

Crowd scenes must represent this rich

diversity and reflect a range of responses to Jesus among the crowd as among

their leaders.

·

The Jewishness of Jesus and his followers

must be taken seriously. They must be portrayed as Jews among Jews and not set

apart by means of costuming or makeup.

·

Stereotypes of Jews and Judaism (e.g.

depicting Jews as avaricious) must be avoided. [This is especially important in

portraying Judas, whose name means Jew, and who is given money for betraying

Jesus.]

·

The Pharisees are not mentioned in the

gospel accounts of Jesus’ Passion and therefore should not be depicted as

responsible for his death. The Jews most directly implicated in the death of

Jesus are the Temple priests.

·

Roman soldiers should be on stage

throughout the play to keep before the audience the pervasive and oppressive

reality of Roman occupation.

·

Problematic passages, like Matthew’s “his

blood be on us and on our children” (27:25), that can be misconstrued as

blaming all Jews of all time for the death of Jesus, should be omitted. As a

general rule in these cases, the Bishops suggest that “if one cannot show

beyond reasonable doubt that the particular gospel element selected or

paraphrased will not be offensive or have the potential for negative influence

on the audience for whom the presentation is intended, the element cannot, in

good conscience, be used” (“Criteria,” p. 12).

On January 6, 2004, the Consultative Panel on

Lutheran-Jewish Relations of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

similarly issued a statement urging any Lutheran church presenting a Passion

Play to adhere to their Guidelines for Lutheran-Jewish Relations,

stating that "the New Testament . .

. must not be used as justification for hostility towards present-day

Jews," and that "blame for the death of Jesus should not be

attributed to Judaism or the Jewish people."

In 2003

and 2004 some compared Mel Gibson's recent film The Passion of the Christ

to these kinds of passion plays, but this characterization is hotly disputed;

an analysis of that topic is in the article on The Passion of the Christ.

Despite such fears, there have been no publicized antisemitic incidents

directly attributable to the movie's influence. However, the film's reputation

for antisemitism led to the movie being distributed and well-received

throughout the Muslim world, even in nations that typically suppress public

expressions of Christianity.

Early Christianity

A number

of early and influential Church works — such as the dialogues of Justin Martyr,

the homilies of John Chrysostom, and the testimonies of church father Cyprian —

are strongly anti-Jewish.

During a discussion on the celebration of Easter during

the First Council of Nicaea in AD 325, Roman emperor Constantine said,

...it appeared an unworthy thing that in the celebration

of this most holy feast we should follow the practice of the Jews, who have

impiously defiled their hands with enormous sin, and are, therefore, deservedly

afflicted with blindness of soul. (...) Let us then have nothing in common with

the detestable Jewish crowd; for we have received from our Saviour a different

way.

Prejudice

against Jews in the Roman Empire was formalized in 438, when the Code of

Theodosius II established Roman Catholic Christianity as the only legal

religion in the Roman Empire. The Justinian Code a century later stripped Jews

of many of their rights, and Church councils throughout the sixth and seventh

century, including the Council of Orleans, further enforced anti-Jewish

provisions. These restrictions began as early as 305, when, in Elvira, (now

Granada), a Spanish town in Andalusia, the first known laws of any church

council against Jews appeared. Christian women were forbidden to marry Jews

unless the Jew first converted to Catholicism. Jews were forbidden to extend

hospitality to Catholics. Jews could not keep Catholic Christian concubines and

were forbidden to bless the fields of Catholics. In 589, in Catholic Spain, the

Third Council of Toledo ordered that children born of marriage between Jews and

Catholic be baptized by force. By the Twelfth Council of Toledo (681) a policy

of forced conversion of all Jews was initiated (Liber Judicum, II.2 as given in

Roth). Thousands fled, and thousands of others converted to Roman Catholicism.

Accusations of

deicide

The first accusation that Jews were

responsible for the death of Jesus came in a sermon in 167 CE attributed to

Melito of Sardis entitled Peri Pascha, On the Passover. This

text blames the Jews for allowing King

Herod and Caiaphas to execute Jesus, despite their calling as God's people.

It say "you did not know, O Israel, that this one was the firstborn of

God". The author does not attribute particular blame to Pontius Pilate,

but only mentions that Pilate washed his hands of guilt. The sermon is written

in Greek, so does not use the Latin word for deicide, deicida. At a time

when Christians were widely persecuted, Melito's speech was an appeal to Rome

to spare Christians.

According to a Latin dictionary, the the Latin word deicidas

was used by the fourth century, by Peter Chrystologus in his sermon number 172.

Though not part of Roman Catholic dogma,

many Christians, including members of the clergy, held the Jewish people

collectively responsible for killing Jesus. According to this interpretation,

both the Jews present at Jesus’ death and the Jewish people collectively and

for all time had committed the sin of deicide, or God-killing.

Antisemitism in Europe during the Middle Ages

Persecution of

Jews in the Middle Ages

There was continuity in the hostile

attitude to Judaism from the ancient Roman Empire into the medieval period.

From the 9th century CE the Islamic world imposed dhimmi laws on both Christian

and Jewish minorities. In the later Middle Ages in Europe there was full-scale

persecution in many places, with blood libels, expulsions, forced conversions

and massacres. A main justification of prejudice against Jews in Europe was

religious.

Antisemitism

was widespread in Europe during the Middle Ages. In those times, a main cause

of prejudice against Jews in Europe was the religious one. Although not part of

Roman Catholic dogma, many Christians,

including members of the clergy, held the Jewish people collectively

responsible for the death of Jesus, a practice originated by Melito of

Sardis. Among socio-economic factors were restrictions by the authorities. Local rulers and church officials closed

the doors for many professions to the Jews, pushing them into occupations

considered socially inferior such as accounting, rent-collecting and

moneylending, which was tolerated then as a "necessary evil". During

the Black Death, Jews were accused as being the cause, and were often killed.

There were expulsions of Jews from England, France, Germany, Portugal and Spain

during the Middle Ages as a result of antisemitism.

Starting

in the 12th century and continued up through the 19th century, there were Christians who believed that

some (or all) Jews possessed magical powers. Some believed they had gained

these magical powers by making a deal with the devil. In Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice, considered to be one

of the greatest romantic comedies of all time, the villain Shylock was a Jewish

moneylender. By the end of the play he is mocked on the streets after his

daughter elopes with a Christian. Shylock, then, compulsorily converts to

Christianity as a part of a deal gone wrong. This has raised profound

implications regarding Shakespeare and anti-semitism. During the Middle

Ages, the story of Jephonias, the Jew who tried to overturn Mary's funeral

bier, changed from his converting to Christianity into his simply having his

hands cut off by an angel.

A 15th century German woodcut

showing an alleged host desecration. In the first panel the hosts are stolen;

in the second the hosts bleed when pierced by a Jew; in the third the Jews are

arrested; and in the fourth they are burned alive.

On many occasions, Jews were accused of a

blood libel, the supposed drinking

of blood of Christian children in mockery of the Christian Eucharist. Jews were subject to a wide range of legal

restrictions throughout the Middle Ages, some of which lasted until the end of

the 19th century. Jews were excluded from many trades, the occupations varying

with place and time, and determined by the influence of various non-Jewish

competing interests. Often Jews were barred from all occupations but

money-lending and peddling, with even these at times forbidden.

Restriction to

marginal occupations

Among socio-economic factors were restrictions

by the authorities. Local rulers and church officials closed many professions

to the Jews, pushing them into marginal occupations considered socially

inferior, such as tax and rent collecting and moneylending, tolerated then as a

"necessary evil". Catholic doctrine of the time held that lending

money for interest was a sin, and forbidden to Christians. Not being subject to

this restriction, Jews dominated this business. The Torah and later

sections of the Hebrew Bible criticise Usury but interpretations of the

Biblical prohibition vary. Since few

other occupations were open to them, Jews were motivated to take up money

lending. This was said to show Jews were insolent, greedy, usurers, and

subsequently lead to many negative stereotypes and propaganda. Natural tensions

between creditors (typically Jews) and debtors (typically Christians) were

added to social, political, religious, and economic strains. Peasants who were

forced to pay their taxes to Jews could personify them as the people taking

their earnings while remaining loyal to the lords on whose behalf the Jews

worked.

Disabilities

and restrictions

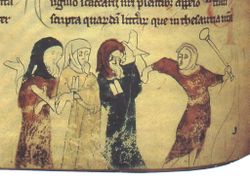

The yellow badge Jews were

forced to wear can be seen in this marginal illustration from an English

manuscript.

Jews were subject to a wide range of

legal restrictions throughout the Middle Ages, some of which lasted until the

end of the 19th century. Jews were excluded from many trades, the occupations

varying with place and time, and determined by the influence of various

non-Jewish competing interests. Often Jews were barred from all occupations but

money-lending and peddling, with even these at times forbidden. The number of

Jews permitted to reside in different places was limited; they were

concentrated in ghettos, and were not allowed to own land; they were subject to

discriminatory taxes on entering cities or districts other than their own, were

forced to swear special Jewish Oaths, and suffered a variety of other measures,

including restrictions on dress.

Clothing

The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 was

the first to proclaim the requirement for Jews to wear something that

distinguished them as Jews. It could be a coloured piece of cloth in the shape

of a star or circle or square, a hat (Judenhut), or a robe. In many localities,

members of the medieval society wore badges to distinguish their social status.

Some badges (such as guild members) were prestigious, while others ostracised

outcasts such as lepers, reformed heretics and prostitutes. Jews sought to

evade the badges by paying what amounted to bribes in the form of temporary

"exemptions" to kings, which were revoked and re-paid whenever the

king needed to raise funds.

The Crusades

The Crusades were a series of military

campaigns sanctioned by the papacy that took place from the end of the 11th

century until the 13th century. They began as endeavors to recapture Jerusalem from the Muslims but developed into

territorial wars. The mobs accompanying the first three Crusades, and

particularly the People's Crusade

accompanying the first Crusade, attacked

the Jewish communities in Germany, France, and England, and put many Jews to

death. Entire communities, like those of Treves, Speyer, Worms, Mayence, and

Cologne, were slain by a mob army. About

12,000 Jews are said to have perished in the Rhineland cities alone between May

and July, 1096. Before the Crusades the Jews had practically a monopoly of

trade in Eastern products, but the closer connection between Europe and the

East brought about by the Crusades raised up a class of merchant traders among

the Christians, and from this time onward restrictions

on the sale of goods by Jews became frequent. The religious zeal fomented by

the Crusades at times burned as fiercely against the Jews as against the

Muslims, though attempts were made by bishops during the first Crusade and the

papacy during the second Crusade to stop Jews from being attacked. Both

economically and socially the Crusades were disastrous for European Jews.

They prepared the way for the anti-Jewish legislation of Pope Innocent III, and

formed the turning point in the medieval history of the Jews.

In the

County of Toulouse (now part of southern France) the Jews were received on good

terms until the Albigensian Crusade. Toleration

and favour shown to the Jews was one of the main complaints of the Roman Church

against the Counts of Toulouse. Following the Crusaders' successful wars

against Raymond VI and Raymond VII, the

counts were required to discriminate against Jews like other Christian

rulers. In 1209, stripped to the waist and barefoot, Raymond VI was obliged to

swear that he would no longer allow Jews

to hold public office. In 1229 his son Raymond VII, underwent a similar

ceremony where he was obliged to prohibit

the public employment of Jews, this time at Notre Dame in Paris. Explicit

provisions on the subject were included in the Treaty of Meaux (1229). By the

next generation a new, zealously Catholic, ruler was arresting and imprisoning Jews for no crime, raiding their houses,

seizing their cash, and removing their religious books. They were then released

only if they paid a new "tax". A historian has argued that organised and official persecution of the

Jews became a normal feature of life in southern France only after the

Albigensian Crusade because it was only then that the Church became powerful

enough to insist that measures of discrimination be applied.

The Demonizing

of the Jews

From

around the 12th century through the 19th there

were Christians who believed that some (or all) Jews possessed magical powers;

some believed that they had gained these magical powers from making a deal with

the devil.

Blood Libels

On many occasions, Jews were accused of a

blood libel, the supposed drinking of blood of Christian children in mockery of

the Christian Eucharist. (Early Christians had been

accused of a similar practice based on pagan misunderstanding of the Eucharist

ritual.) According to the authors of these blood libels, the 'procedure' for

the alleged sacrifice was something like this: a child who had not yet reached

puberty was kidnapped and taken to a hidden place. The child would be tortured

by Jews, and a crowd would gather at the place of execution (in some accounts

the synagogue itself) and engage in a mock tribunal to try the child. The child

would be presented to the tribunal naked and tied and eventually be condemned

to death. In the end, the child would be crowned with thorns and tied or nailed

to a wooden cross. The cross would be raised, and the blood dripping from the

child's wounds would be caught in bowls or glasses and then drunk. Finally, the

child would be killed with a thrust through the heart from a spear, sword, or

dagger. Its dead body would be removed from the cross and concealed or disposed

of, but in some instances rituals of black magic would be performed on it. This

method, with some variations, can be found in all the alleged Christian

descriptions of ritual murder by Jews.

The story of William of Norwich (d. 1144)

is often cited as the first known accusation of ritual murder against Jews. The

Jews of Norwich, England were accused of murder after a Christian boy, William,

was found dead. It was claimed that the Jews had tortured and crucified their

victim. The legend of William of Norwich became a cult, and the child acquired

the status of a holy martyr. Recent analysis has cast doubt on whether this was

the first of the series of blood libel accusations but not on the contrived and

antisemitic nature of the tale.

During the Middle Ages blood libels were

directed against Jews in many parts of Europe. The believers of these

accusations reasoned that the Jews, having crucified Jesus, continued to thirst

for pure and innocent blood and satisfied their thirst at the expense of

innocent Christian children. Following this logic, such charges were

typically made in Spring around the time of Passover, which approximately coincides

with the time of Jesus' death.

The

story of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln (d. 1255) said that after the boy was

dead, his body was removed from the cross and laid on a table. His belly was

cut open and his entrails removed for some occult purpose, such as a divination

ritual. The story of Simon of Trent (d. 1475) emphasized how the boy was held

over a large bowl so all his blood could be collected.

Expulsions

from France and England

The practice of expelling the Jews

accompanied by confiscation of their property, followed by temporary

readmissions for ransom, was utilized to enrich the French crown during

12th-14th centuries. The most notable such expulsions were: from Paris by

Philip Augustus in 1182, from the entirety of France by Louis IX in 1254, by

Charles IV in 1306, by Charles V in 1322, by Charles VI in 1394.

To finance his war to conquer Wales, Edward

I of England taxed the Jewish moneylenders. When the Jews could no longer pay,

they were accused of disloyalty. Already restricted to a limited number of

occupations, the Jews saw Edward abolish their "privilege" to lend

money, choke their movements and activities and were forced to wear a yellow

patch. The heads of Jewish households were then arrested, over 300 of them

taken to the Tower of London and executed, while others killed in their homes.

The complete banishment of all Jews from the country in 1290 led to thousands

killed and drowned while fleeing and the absence of Jews from England for three

and a half centuries, until 1655, when Oliver Cromwell reversed the policy.

The Black

Death

As the Black Death epidemics devastated

Europe in the mid-14th century, annihilating more than a half of the

population, Jews were taken as scapegoats. Rumors spread that they caused the disease by deliberately poisoning

wells. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed by violence, in

particular in the Iberian peninsula and in the Germanic Empire. In Provence, 40

Jews were burnt in Toulon as soon as April 1348. "Never mind that Jews were not immune from the ravages of the

plague ; they were tortured until they "confessed" to crimes

that they could not possibly have committed. In one such case, a man named

Agimet was ... coerced to say that Rabbi Peyret of Chambery (near Geneva) had

ordered him to poison the wells in Venice, Toulouse, and elsewhere. In the

aftermath of Agimet’s "confession," the Jews of Strasbourg were

burned alive on February 14, 1349.

Although

the Pope Clement VI tried to protect them by the July 6, 1348 papal bull and

another 1348 bull, several months later, 900

Jews were burnt in Strasbourg, where the plague hadn't yet affected the city. Clement

VI condemned the violence and said those who blamed the plague on the Jews

(among whom were the flagellants) had been "seduced by that liar, the

Devil."

History

of Antisemitism in the Early Modern Period

Anti-Judaism

and the Reformation

Luther's 1543 pamphlet On the Jews and Their Lies

Martin

Luther, an Augustinian monk and an ecclesiastical reformer whose teachings

inspired the Reformation, wrote antagonistically about Jews in his book On

the Jews and their Lies, which describes the Jews in extremely harsh terms,

excoriates them, and provides detailed recommendations for a pogrom against

them and their permanent oppression and/or expulsion. According to Paul

Johnson, it "may be termed the first work of modern antisemitism, and a

giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust." In his final sermon

shortly before his death, however, Luther preached "We want to treat them

with Christian love and to pray for them, so that they might become converted

and would receive the Lord." Still, Luther's harsh comments about the Jews

are seen by many as a continuation of medieval Christian antisemitism.

Expulsions

In 1492,

Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile issued General Edict on the

Expulsion of the Jews from Spain and many Sephardi Jews fled to the Ottoman

Empire, some to the Land of Israel. The Kingdom of Portugal followed suite and

in December 1496, it was decreed that any

Jew who did not convert to Christianity would be expelled from the country.

However, those expelled could only leave the country in ships specified by the

King. When those who chose expulsion arrived at the port in Lisbon, they were

met by clerics and soldiers who used force, coercion, and promises in order to baptize

them and prevent them from leaving the country. This period of time

technically ended the presence of Jews in Portugal. Afterwards, all converted Jews and their descendants

would be referred to as "New Christians" or Marranos, and they were

given a grace period of thirty years in which no inquiries into their faith

would be allowed; this was later to extended to end in 1534. A popular riot

in 1504 would end in the death of two thousand Jews; the leaders of this riot

were executed by Manuel.

Eighteenth

Century

In 1744,

Frederick II of Prussia limited Breslau to only ten so-called

"protected" Jewish families and encouraged similar practice in other

Prussian cities. In 1750 he issued Revidiertes General Privilegium und

Reglement vor die Judenschaft: the

"protected" Jews had an alternative to "either abstain from

marriage or leave Berlin" (quoting Simon Dubnow). In the same year,

Archduchess of Austria Maria Theresa ordered Jews out of Bohemia but soon

reversed her position, on condition that Jews

pay for readmission every ten years. This extortion was known as malke-geld

(queen's money). In 1752 she

introduced the law limiting each Jewish

family to one son. In 1782, Joseph II abolished most of persecution

practices in his Toleranzpatent, on the condition that Yiddish and Hebrew are eliminated from

public records and judicial autonomy is annulled. Moses Mendelssohn wrote

that "Such a tolerance... is even more dangerous play in tolerance than

open persecution".

Antisemitism in 19th and 20th Century (Catholicism)

Throughout the 19th century and into the

20th, the Roman Catholic Church still incorporated strong antisemitic elements,

despite increasing attempts to separate anti-Judaism, the opposition to the

Jewish religion on religious grounds, and racial antisemitism. Pope Pius VII (1800-1823) had the walls of

the Jewish Ghetto in Rome rebuilt after the Jews were released by Napoleon, and

Jews were restricted to the Ghetto through the end of the papacy of Pope Pius

IX (1846-1878), the last Pope to rule Rome. Additionally, official organizations such as the Jesuits banned

candidates "who are descended from the Jewish race unless it is clear that

their father, grandfather, and great-grandfather have belonged to the Catholic

Church" until 1946. Brown University historian David Kertzer, working

from the Vatican archive, has further argued in his book The Popes Against

the Jews that in the 19th and 20th

century the Roman Catholic Church adhered to a distinction between "good

antisemitism" and "bad antisemitism". The "bad" kind promoted hatred of Jews because of their

descent. This was considered un-Christian because the Christian message was

intended for all of humanity regardless of ethnicity; anyone could become a

Christian. The "good" kind criticized alleged Jewish conspiracies to

control newspapers, banks, and other institutions, to care only about

accumulation of wealth, etc. Many Catholic bishops wrote articles criticizing

Jews on such grounds, and, when accused of promoting hatred of Jews, would

remind people that they condemned the "bad" kind of antisemitism.

Kertzer's work is not, therefore, without critics; scholar of Jewish-Christian

relations Rabbi David G. Dalin, for example, criticized Kertzer in the Weekly

Standard for using evidence selectively. The Second Vatican Council, the Nostra

Aetate document, and the efforts of Pope John Paul II have helped reconcile

Jews and Catholicism in recent decades, however. The controversial document

Dabru Emet was issued by many American Jewish scholars in 2000 as a statement

about Jewish-Christian relations. This document says, "Nazism was not a

Christian phenomenon. Without the long history of Christian anti-Judaism and

Christian violence against Jews, Nazi ideology could not have taken hold nor

could it have been carried out."

Antisemitism and the Muslim world

The Qur'an and other Muslim writings depict

Jews as having failed to accept God's message for them. For hundreds of

years, they lived as dhimmis under discriminatory regimes in Muslim lands. In occasional pogroms, such as Fez in 1033

and Granada in 1066, Muslims would kill thousands of Jews at a time.

Antisemitism in Muslim countries increased in the 19th century. The nature

and extent of antisemitism among Muslims, and its relation to anti-Zionism, are

hotly-debated issues in contemporary Middle East politics.

Jews in Islamic texts

|

And abasement and poverty were pitched upon them, (Quran, verse 2:61) |

The

Qur'an contains attacks on Jews for their refusal to recognize Muhammad as a

prophet of God, and the Muslim holy text has defined Arab and Muslim attitudes

towards Jews to this day, especially in the periods when Islamic fundamentalism

was on the rise. During Muhammad's life, Jews lived in

the Arabian Peninsula, especially in and around Medina. They refused to accept Muhammad's teachings, and eventually he fought

them after they broke the treaty of Hudaibiya and defeated them, killing the

majority of one of Medinah's Jewish tribes.

The words "humility" and

"humiliation" occur frequently in the Qur'an and later Muslim

literature to describe the condition to which Jews must be reduced as a just

punishment for their past rebelliousness -- the punishment that shows itself in

the defeat they suffered at the hands of Christians and Muslims. The

standard Quranic reference to Jews is verse 2:61,

Cowardice, greed, and chicanery are but a few of the

characteristics that the Qur'an ascribes to the Jews. The Qur'an further

associates Jews with interconfessional strife and rivalry (Qur'an 2:113). It

claims that Jews believe that they alone are beloved of God (Qur'an 5:18) and

that only they will achieve salvation.(2:111) According to the Qur'an, Jews

blasphemously claim that Ezra is the son of God, as Christians claim Jesus is,

(Qur'an 9:30) and that God’s hand is fettered. (Qur'an 5:64) Together with the

pagans, Jews are, “the most vehement of men in enmity to those who believe”.

(Qur'an 5:82) Some of those who are Jews, "pervert words from their

meanings", (Qur'an 4:44) have committed wrongdoing, for which God has

"forbidden some good things that were previously permitted them", (Qur'an

4:160) they listen for the sake of mendacity,(Qur'an 5:41) and some of them

have committed usury and will receive "a painful doom." (Qur'an

4:161) The Qur'an gives credence to the Christian claim of Jews scheming

against Jesus, "...but God also schemed, and God is the best of

schemers."(Qur'an 3:54) In the Muslim view, the crucifixion of Jesus was

an illusion, and thus the Jewish plots against him ended in complete failure.

In numerous verses (3:63; 3:71; 4:46; 4:160-161; 5:41-44, 5:63-64, 5:82; 6:92) the

Qur'an accuses Jews of deliberately obscuring and perverting scripture.

The traditional biographies of Muhammad

recount the expulsion of the Jewish tribes of Banu Qaynuqa and Banu Nadir from

Medina, the massacre of Banu Qurayza, and Muhammad's attack on the Jews of

Khaybar. The rabbis of Medina are singled out as "men whose malice and

enmity was aimed at the Apostle of God [i.e., Muhammad]". Jews appear in the biographies of Muhammad

not only as malicious, but also deceitful, cowardly, and totally lacking in

resolve. Their ignominy is presented in marked contrast to Muslim heroism, and

in general conforms to the Quranic image of people with "wretchedness and

baseness stamped upon them".(Qur'an 2:61)

The hadith

continue the theme of Jewish hostility toward Muslims. One hadith says: "A Jew will not be found alone with a Muslim

without plotting to kill him." According to another hadith, Muhammad

said: "The Hour will not be

established until you fight with the Jews, and the stone behind which a Jew

will be hiding will say. "O Muslim! There is a Jew hiding behind me, so

kill him.'"(Sahih Bukhari 4:52:177) This hadith has been quoted

countless times, and has become part of the charter of Hamas.

Pre-modern times

The portrayal of the Jews in the early

Islamic texts played a key role in shaping the attitudes towards them in the

Muslim societies. According to Jane Gerber, "the Muslim is continually

influenced by the theological threads of anti-Semitism embedded in the earliest

chapters of Islamic history." In the

light of the Jewish defeat at the hands of Muhammad, Muslims traditionally

viewed Jews with contempt and as objects of ridicule. Jews were seen as

hostile, cunning, and vindictive, but nevertheless weak and ineffectual.

Cowardice was the quality most frequently attributed to Jews. Another

stereotype associated with the Jews was their alleged propensity to trickery

and deceit. While most anti-Jewish polemicists saw those qualities as

inherently Jewish, ibn Khaldun attributed them to the mistreatment of Jews at

the hands of the dominant nations. For that reason, says ibn Khaldun, Jews "are renowned, in every age and

climate, for their wickedness and their slyness".

Some

Muslim writers have inserted racial overtones in their anti-Jewish polemics.

Al-Jahiz speaks of the deterioration of

the Jewish stock due to excessive inbreeding. Ibn Hazm also implies racial

qualities in his attacks on the Jews. However, these were exceptions, and the

racial theme left little or no trace in the medieval Muslim anti-Jewish writings.

Islamic law demands that when under Muslim

rule non-Muslims should be treated as dhimmis. Dhimmis were granted

protection of life (including against other Muslim states), rights to reside in

designated areas, worship, and work or trade. They were exempted from military

service and Muslim religious duties, personal law, and some taxes. Certain

conditions were imposed upon them, including paying the poll tax (jizyah) and

land taxes as set by Muslim authorities. At the same time they were subject to

various restrictions in relation to Muslims and Islam. Muslim men could marry

dhimmi women and own dhimmi slaves, but the opposite was not true. They were

forbidden to desecrate the Qur'an or defame Muhammad, and were forbidden to

proselytize. Jews and other non-Muslims were at times subjected to a number of

other restrictions such as limitations on dress, riding horses or camels,

carrying arms, holding public office, building or repairing places of worship,

mourning loudly, wearing shoes outside a Jewish ghetto, etc.

Anti-Jewish sentiments usually flared up at

times of the Muslim political or military weakness or when Muslims felt that

some Jews had overstepped the boundary of humiliation prescribed to them by the

Islamic law. In Moorish Spain, ibn Hazm and Abu Ishaq focused their

anti-Jewish writings on the latter allegation. This was also the chief

motivation behind the 1066 Granada massacre, when "[m]ore than 1,500

Jewish families, numbering 4,000 persons, fell in one day", and in Fez in

1033, when 6,000 Jews were killed. There were further massacres in Fez in 1276

and 1465.

Islamic

law does not differentiate between Jews and Christians in their status as

dhimmis. According to Bernard Lewis, the normal practice of Muslim governments

until modern times was consistent with this aspect of sharia law. This view is

countered by Jane Gerber, who maintains that of all dhimmis, Jews had the lowest status. Gerber maintains that

this situation was especially pronounced in the latter centuries, when

Christian communities enjoyed protection, unavailable to the Jews, under the

provisions of Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire. For example, in 18th-century

Damascus, a Muslim noble held a festival, inviting to it all social classes in

descending order, according to their social status: the Jews outranked only the peasants and prostitutes. In 1865, when the

equality of all subjects of the Ottoman Empire was proclaimed, Cevdet Pasha, a

high-ranking official observed: "whereas in former times, in the Ottoman

State, the communities were ranked, with the Muslims first, then the Greeks,

then the Armenians, then the Jews, now all of them were put on the same level.

Some Greeks objected to this, saying: 'The government has put us together with

the Jews. We were content with the supremacy of Islam.'"

According to Paul Johnson,

"In theory, ...

the status of Jewish dhimmi under Moslem rule was worse than under the

Christians, since their right to practise their religion, and even their right

to live, might be arbitrarily removed at any time. In practice, however, the

Arab warriors ... had no wish to exterminate literate and industrious Jewish

communities who provided them with reliable tax incomes and served them in

innumerable ways. ... The Arab Moslems were slow to develop any religious

animus against the Jews. In Moslem eyes, the Jews had sinned by rejecting

Mohammed's claims, but they had not crucified him."

"Always, in the

background, there was the menace of anti-Semitism. It is described in the

genizah documents by the word sinuth, hatred. ... Parts of Islam were

much worse than others for Jews. Morocco was fanatical. So was northern Syria.

... Goitein concludes that the evidence does not support the view that in

Egypt, at least, anti-Semitism was endemic or serious. But then Egypt under the

Fatimids and Ayyubids was a refuge for persecuted Jews (and others) from all

over the world."

Some scholars have questioned the correctness of the term

"antisemitism" to Muslim culture in pre-modern times. Bernard Lewis

distinguishes between "normal" prejudice against and

"normal" persecution of different nations or beliefs on the one hand,

and "antisemitism" on the other hand. Lewis confines his definition

of antisemitism to "the special and peculiar hatred of the Jews, which

derives its unique power from the historical relationship between Judaism and

Christianity, and the role assigned by Christians to the Jews in their writings

and beliefs". From this premise Lewis concludes that until

modern times "Arabs have not in fact been anti-Semitic as that word is

used in the West... because for the most part they are not Christians."

Claude Cahen argues that, while

prejudice and hostility existed in the Islamic world, there was no antisemitism

since there was scarcely any difference in the treatment accorded to Christians

and Jews. Robert Chazan and Alan Davies argue that the most obvious difference

between pre-modern Islam and pre-modern Christendom was the "rich melange

of racial, ethic, and religious communities" in Islamic countries, within

which "the Jews were by no means obvious as lone dissenters, as they had

been earlier in the world of polytheism or subsequently in most of medieval

Christendom." According to Chazan and Davies, this lack of uniqueness

ameliorated the circumstances of Jews in the medieval world of Islam.

Disputing this view, Shelomo Dov Goitein argues that the

existence of antisemitism in pre-modern Islam is supported by documentary

evidence: "[t]he Genizah material confirms the existence of a discernible

form of anti-Judaism in the time and the place considered here, but that form

of 'anti-Semitism', if we may use this term, appears to have been local and

sporadic rather than general and endemic." Leon Poliakov also maintains

that the term "antisemitism" is applicable to the hostility against

Jews in pre-modern Islam, even if "only with qualifications".

According to Norman Stillman, antisemitism, understood as hatred of Jews as

Jews, "did exist in the medieval Arab world even in the period of greatest

tolerance".

What

is a Dhimmi?

A dhimmi was a free, non-Muslim subject of a state governed in

accordance with sharia — Islamic law. A dhimmi is a person of the dhimma,

a term which refers in Islamic law to a pact contracted between non-Muslims and

authorities from their Muslim government. This status was originally only made

available to non-Muslims who were People of the Book (i.e. Jews and

Christians), but was later extended to include Sikhs, Zoroastrians, Mandeans,

and, in some areas, Hindus and Buddhists. The status of dhimmi was one of legal

and social inferiority, and applied to millions of people living from the

Atlantic Ocean to India from the 7th century until modern times. Over time,

many dhimmis converted to Islam. Most conversions were voluntary and happened

for a number of different reasons but forced conversion played a role in some

later periods of Islamic history, mostly in the 12th century under the Almohad

dynasty of North Africa and al-Andalus as well as in Persia where Shi'a Islam

is dominant.

Modern period

19th century

Historian

Martin Gilbert writes that it was in the 19th century that the position of Jews

worsened in Muslim countries.There was a

massacre of Jews in Baghdad in 1828. In 1839, in the eastern Persian city of

Meshed, a mob burst into the Jewish Quarter, burned the synagogue, and

destroyed the Torah scrolls. It was only by forcible conversion that a massacre

was averted. There was another massacre in Barfurush in 1867. In 1840, the Jews of Damascus were falsely

accused of having murdered a Christian monk and his Muslim servant and of

having used their blood to bake Passover bread or Matza. A Jewish barber was

tortured until he "confessed"; two other Jews who were arrested died

under torture, while a third converted to Islam to save his life. Throughout

the 1860s, the Jews of Libya were subjected to what Gilbert calls punitive

taxation. In 1864, around 500 Jews were killed in Marrakech and Fez in Morroco.

In 1869, 18 Jews were killed in Tunis, and an Arab mob looted Jewish homes and

stores, and burned synagogues, on Jerba Island. In 1875, 20 Jews were killed by

a mob in Demnat, Morocco; elsewhere in Morocco, Jews were attacked and killed

in the streets in broad daylight. In 1891, the leading Muslims in Jerusalem

asked the Ottoman authorities in Constantinople to prohibit the entry of Jews

arriving from Russia. In 1897, synagogues were ransacked and Jews were murdered

in Tripolitania.

Benny

Morris writes that one symbol of Jewish degradation was the phenomenon of stone-throwing at Jews by Muslim children.

Morris quotes a 19th century traveler:

"I have seen a little fellow of six years old, with

a troop of fat toddlers of only three and four, teaching [them] to throw stones

at a Jew, and one little urchin would, with the greatest coolness, waddle up to

the man and literally spit upon his Jewish gaberdine. To all this the Jew is

obliged to submit; it would be more than his life was worth to offer to strike

a Mahommedan."

According to Mark Cohen in The Oxford Handbook of

Jewish Studies, most scholars conclude

that Arab anti-Semitism in the modern world arose in the nineteenth century,

against the backdrop of conflicting Jewish and Arab nationalism, and was

imported into the Arab world primarily by nationalistically minded Christian

Arabs (and only subsequently was it "Islamized").

20th century

The Eternal Jew (German: Der

ewige Jude): 1937 German poster advertising an antisemitic Nazi movie.

There

were Nazi-inspired pogroms in

Algeria in the 1930s, and massive attacks on the Jews in Iraq and Libya in the

1940s. Pro-Nazi Muslims slaughtered

dozens of Jews in Baghdad in 1941. The massacres of Jews in Muslim countries

continued into the 20th century. Martin Gilbert writes that 40 Jews were

murdered in Taza, Morocco in 1903. In 1905, old laws were revived in Yemen

forbidding Jews from raising their voices in front of Muslims, building their

houses higher than Muslims, or engaging in any traditional Muslim trade or

occupation. The Jewish quarter in Fez was almost destroyed by a Muslim mob in

1912.

George

Gruen attributes the increased animosity

towards Jews in the Arab world to several factors, including the breakdown of the Ottoman Empire and

traditional Islamic society; domination by Western colonial powers under

which Jews gained a disproportionatly

larger role in the commercial, professional, and administrative life of the

region; the rise of Arab nationalism,

whose proponents sought the wealth and positions of local Jews through

government channels; resentment over

Jewish nationalism and the Zionist movement; and the readiness of unpopular

regimes to scapegoat local Jews for

political purposes.

Antagonism and violence increased still

further as resentment against Zionist efforts in the British Mandate of

Palestine spread. Anti-Zionist propaganda in the Middle East frequently

adopts the terminology and symbols of the Holocaust to demonize Israel and its

leaders. At the same time, Holocaust

denial and Holocaust minimization

efforts have found increasingly overt acceptance as sanctioned historical

discourse in a number of Middle Eastern countries. Arabic- and Turkish-edition

of Hitler's Mein Kampf and The Protocols of the Elders of Zion have

found an audience in the region with limited critical response by local

intellectuals and media.

According

to Robert Satloff, Muslims and Arabs

were involved both as rescuers and perpetrators of the Holocaust during Italian

and German Nazi occupation of Morocco, Tunisia and Libya.

Antisemitism has been reportedly found in

Arab and Iranian media and schoolbooks. For example, Center for Religious

Freedom of Freedom House analyzed a set of Saudi Ministry of Education

textbooks in use during the current academic year in Islamic studies courses

for elementary and secondary students. Among statements and ideas found against

non-Wahhabi Muslims and "non-believers" were ideas that teach Muslims

to "hate" Christians, Jews, "polytheists" and other

"unbelievers," including non-Wahhabi Muslims, though, incongruously,

not to treat them "unjustly"; teach the infamous forgeries, The

Protocols of the Elders of Zion, as historical fact and relate modern events to

it; teach that "Jews and the Christians are enemies of the [Muslim]

believers" and that "the clash" between the two realms is

perpetual; instruct that "fighting between Muslims and Jews" will

continue until Judgment Day, and that the Muslims are promised victory over the

Jews in the end; cite a selective teaching of violence against Jews, while in

the same lesson, ignoring the passages of the Qur'an and hadiths that counsel

tolerance; include a map of the Middle East that labels Israel within its

pre-1967 borders as "Palestine: occupied 1948"; discuss Jews in

violent terms, blaming them for virtually all the "subversion" and

wars of the modern world. A 38-page overview of Saudi Arabia's curriculum has

been released to the press by the Hudson Institute.

Racial antisemitism

Racial

antisemitism replaced the hatred of Judaism with the hatred of Jews as a group.

In the context of the Industrial Revolution, following the emancipation of the

Jews, Jews rapidly urbanized and experienced a period of greater social

mobility. With the decreasing role of religion in public life tempering

religious antisemitism, a combination of growing nationalism, the rise of

eugenics, and resentment at the socio-economic success of the Jews led to the

newer, and more virulent, racist antisemitism.

New

Antisemitism

In

recent years some scholars have advanced the concept of New antisemitism,

coming simultaneously from the left, the far right, and radical Islam, which

tends to focus on opposition to the emergence of a Jewish homeland in the State

of Israel, and argue that the language of Anti-Zionism and criticism of Israel

are used to attack the Jews more broadly. In this view, the proponents of the

new concept believe that criticisms of Israel and Zionism are often

disproportionate in degree and unique in kind, and attribute this to

antisemitism. The concept has been criticized by those who argue it is used to

stifle debate and deflect attention from legitimate criticism of the State of

Israel, and, by associating anti-Zionism with antisemitism, is intended to

taint anyone opposed to Israeli actions and policies.

Bans on kosher

slaughter

The kosher slaughter of animals is

currently banned in Norway, Switzerland and Sweden, and partially banned in

Holland (for older animals only, who are considered to take longer to lose

consciousness). The Swiss banned kosher slaughter in 1902 and saw an

antisemitic backlash against a proposal to lift the ban a century later. Both

Holland and Switzerland have considered extending the ban in order to prohibit importing kosher products. The

former chief rabbi of Norway, Michael Melchior, argues that antisemitism is a motive for the bans:

"I won't say this is the only motivation, but it's certainly no

coincidence that one of the first things Nazi Germany forbade was kosher

slaughter. I also know that during the original debate on this issue in Norway,

where shechitah has been banned since 1930, one of the parliamentarians said

straight out, 'If they don't like it,

let them go live somewhere else.'"

Antisemitism and specific countries

Antisemitism

in the 21st century

According

to the 2005 U.S. State Department Report on Global Anti-Semitism, antisemitism

in Europe has increased significantly in recent years. Beginning in 2000, oral

attacks directed against Jews increased while incidents of vandalism (e.g. graffiti, fire bombings of Jewish schools,

desecration of synagogues and cemeteries) surged. Physical assaults including beatings, stabbings and other violence

against Jews in Europe increased markedly, in a number of cases resulting in

serious injury and even death.

On

January 1, 2006, Britain's chief rabbi, Sir Jonathan Sacks, warned that what he

called a "tsunami of antisemitism"

was spreading globally. In an interview with BBC's Radio Four, Sacks said that antisemitism was on the rise in Europe,

and that a number of his rabbinical colleagues had been assaulted, synagogues desecrated, and Jewish schools burned to the

ground in France. He also said that: "People are attempting to silence and even ban Jewish societies on campuses

on the grounds that Jews must support the state of Israel, therefore they

should be banned, which is quite extraordinary because ... British Jews see

themselves as British citizens. So it's that kind of feeling that you don't

know what's going to happen next that's making ... some European Jewish

communities uncomfortable."

Much of the new European antisemitic

violence can actually be seen as a spill over from the long running

Israeli-Arab conflict since the majority of the perpetrators are from the large

immigrant Arab communities in European cities. According to The Stephen

Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism and Racism, most

of the current antisemitism comes from militant Islamist and Muslim groups, and

most Jews tend to be assaulted in countries where groups of young Muslim

immigrants reside.

Similarly,

in the Middle East, anti-Zionist propaganda frequently adopts the terminology

and symbols of the Holocaust to demonize Israel and its leaders — for instance,

comparing Israel's treatment of the

Palestinians to Nazi Germany's treatment of Jews. At the same time, Holocaust denial and Holocaust minimization

efforts find increasingly overt acceptance as sanctioned historical discourse

in a number of Middle Eastern countries.

On April

3, 2006, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights announced its finding that incidents of antisemitism are a

"serious problem" on college campuses throughout the United States.

The Commission recommended that the U.S. Department of Education's Office for

Civil Rights protect college students from antisemitism through vigorous

enforcement of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and further recommended

that Congress clarify that Title VI applies to discrimination against Jewish

students.

On

September 19, 2006, Yale University founded The Yale Initiative for

Interdisciplinary Study of Antisemitism, the first North American

university-based center for study of the subject, as part of its Institution

for Social and Policy Studies. Director Charles Small of the Center cited the

increase in antisemitism worldwide in recent years as generating a "need

to understand the current manifestation of this disease".

Far-right groups have been on the rise in

Germany, and especially in the formerly communist Eastern Germany. Israeli

Ambassador Shimon Stein warned in October 2006 that Jews in Germany feel

increasingly "unsafe," stating that they "are not able to live a

normal Jewish life" and that heavy security surrounds most synagogues or

Jewish community centers.