John Henry

USPS 1996 John Henry stamp

John Henry is an American mythical (usually African-American) folk

hero, who has been the subject of numerous songs, stories, plays, and novels.

In

the late 1800s, as the country recovered from the Civil War, railroad tracks

began to stitch the nation together. This made it possible to go from ocean to

ocean in under a week, where it might have earlier taken up to six months.

Among the men that built the railroads, John Henry stands tall, broad shoulders

above the rest. Little can be said for certain about the facts of John Henry's

life, but his tale has become the stuff of myth. He has embodied the spirit of

growth in America for over a century. But his legacy cannot be solely summed up

in the image of a man with a hammer, a former slave representing the strength

and drive of a country in the process of building itself. Something within his story

established John Henry as a fixture of the popular imagination. He has been the

subject of novels, a postage stamp and even animated films. Above all,

"John Henry" is the single most well-known and often-recorded

American folk song.

Though

the story of John Henry sounds like the quintessential tall tale, it is

certainly based, at least in part, on historical circumstance. There are

disputes as to where the legend originates. Some place John Henry in West

Virginia, while recent research suggests Alabama. Still, all share a similar

back-story.

In

order to construct the railroads, companies hired thousands of men to smooth

out terrain and cut through obstacles that stood in the way of the proposed

tracks. One such chore that figures heavily into some of the earliest John

Henry ballads is the blasting of the Big Bend Tunnel -- more than a mile

straight through a mountain in West Virginia.

Steel-drivin'

men like John Henry used large hammers and stakes to pound holes into the rock,

which were then filled with explosives that would blast a cavity deeper and

deeper into the mountain. In the folk ballads, the central event took place

under such conditions. Eager to reduce costs and speed up progress, some tunnel

engineers were using steam drills to power their way into the rock. According

to some accounts, on hearing of the machine, John Henry challenged the steam

drill to a contest. He won, but died of exhaustion, his life cut short by his

own superhuman effort.

Folk researcher Stephen Wade writes that the song was born from the work of driving steel. "In the years before the song became known to the greater American public, it remained in folk possession," he explains. "Black songsters and white hillbilly musicians approached 'John Henry' equipped with a wealth of regional and personal styles." Not surprisingly, the songs caught on and spread to a wider audience. Country music legend Merle Travis heard one version at an early age.

"Ever

since I been big enough to remember hearing anybody sing anything at all, I believe

I've heard that old song about the strong man that hammered hisself to death on

the railroad," Travis said. "There's been dozens and dozens of

different tales about where John Henry comes from."

The

story of John Henry seems to have spoken to just about everyone who heard it,

which probably accounts for why the ballad became so popular. And as the songs

started to become more popular, the legend of the man grew to even larger

proportions. But whatever exaggeration of deed may have ensued, an element of

truth rings through.

John

Cephas is a blues musician from Virginia. "It was a story that was close

to being true," he says. "It's like the underdog overcoming this

powerful force. I mean even into today when you hear it (it) makes you take

pride. I know especially for black people, and for other people from other

ethnic groups, that a lot of people are for the underdog."

Today,

John Henry's legend has grown beyond the songs that helped make him famous.

"Though John Henry most often appears in song," notes Wade, "he

has been depicted in numerous graphic mediums ranging from folk sculpture to

fine art lithography, book illustration to outdoor sculpture." This art

approaches the man himself in several different ways, sometimes placing him in

a historically realistic perspective and focusing on his work and life,

sometimes deifying him. One 1945 illustration by James Daugherty shows John

Henry as a defense worker, supported by other famous black Americans such as

Joe Louis and George Washington Carver.

"Over

the years," Wade continues, "labor lore scholar Archie Green has

researched what he calls 'the visual John Henry.' It's from his work that these

illustrations come, touching, variously, the realms of fine, popular and folk

art."

Thanks

to these works of art, the story of John Henry reaches a new audience that,

today, may not be familiar with the songs that gave rise to the legend.

Wherever people discover John Henry, his influence promises to hold strong.

Mythology

Like other "Big Men" such as Paul Bunyan, Pecos Bill, and Iron

John, John Henry served as a mythical representation of a particular group

within the melting pot of the 19th-century working class. In the most popular

story of his life, Henry is born into the world big and strong. He grows to be

one of the greatest "steel-drivers" in the mid-century push to extend

the railroads across the mountains to the West. The complication of the story

is that, as machine power continued to supplant brute muscle power (both animal

and human), the owner of the railroad buys a steam-powered hammer to do the

work of his mostly black driving crew. In a bid to save his job and the jobs of

his men, John Henry challenges the inventor to a contest: John Henry versus the

steam hammer. John Henry wins, but in the process, he suffers a heart attack

and dies.

In modern depictions John Henry is usually portrayed as hammering down rail

spikes, but older songs instead refer to him driving blasting holes into rock,

part of the process of excavating railroad tunnels and cuttings.

Historical basis

The truth about John Henry is obscured by time and myth, but one legend has

it that he was a slave born in Alabama in the 1840s and fought his famous

battle with the steam hammer along the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in Talcott,

West Virginia. A statue and memorial plaque have been placed along a highway

south of Talcott as it crosses over the tunnel in which the competition may

have taken place.

The railroad historian Roy C. Long found that there were multiple Big Bend

Tunnels along the C&O rail line. Also, the C&O employed multiple black

men who went by the name "John Henry" at the time that those tunnels

were being built. Though he could not find any documentary evidence, he

believes on the basis of anecdotal evidence that the contest between man and

machine did indeed happen at the Talcott, West Virginia site due to the

presence of all three (a man named John Henry, a tunnel named Big Bend, and a

steam-powered drill) at the same time at that place.

The part-time folklorist John Garst has argued that the contest instead

happened at the Coosa Tunnel or the Oak Mountain Tunnel of the Columbus and

Western railroad (now part of Norfolk Southern) in Alabama in 1887. He

conjectures that John Henry may have been a man named Henry born a slave to P.

A. L. Dabney, the father of the chief engineer of that railroad, in 1844.

While he may or may not have been a real character, Henry became an

important symbol of the working man. His story can be seen as an archetypically

tragic illustration of the futility of fighting the technological progress so

evident in the ongoing 19th century upset of traditional physical labor roles.

Some labour advocates interpret the legend as saying that even if you are the

most heroic worker of time-honored practices, management remains more

interested in efficiency and production than in your health and well-being;

though John Henry worked himself to death, they replaced him with a machine

anyway. Thus the legend of John Henry has been a staple of leftist politics,

labor organizing and American counter-culture for well over one hundred years.

References in popular culture

Songs

Songs featuring the story of John Henry have been sung by many blues, folk,

and rock musicians, including Leadbelly (singing both "John Henry"

and a variant entitled "Take This Hammer"), Sonny Terry & Brownie

McGhee, Mississippi John Hurt (in his "Spike Driver Blues" variant of

the song), Woody Guthrie, Big Bill Broonzy, Johnny Cash (singing "The

Legend of John Henry's Hammer"), Ramblin' Jack Elliott, Fred McDowell,

John Fahey (who plays both an instrumental of the original song, and an

instrumental of his own, "John Henry Variation"), Harry Belafonte,

Roberta Flack, Dave Van Ronk, and the Drive-By Truckers (singing "The Day

John Henry Died"). Dave Dudley wrote his own variation called "John

Henry". The Shane Daniel album Yours Truly contains a song called

"The Spirit Of John Henry". Daniel says this song has to do with the

name John Henry not being used in modern songs. Most recently, Bruce

Springsteen performs "John Henry" with a folk band on his 2006 album We

Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions. It was translated into Norwegian as

"Jon Henry" in 1973 by Odd Børretzen. Van Morrison recorded a rock

version of the folk song on his Philospher's Stone album. In addition Henry

Thomas also recorded a version of the song.

Disney film

In 2000, Walt Disney Feature Animation completed a short subject film based

on John Henry, produced at the satellite studio in Orlando, Florida, directed

by Mark Henn and produced by Steven Keller. Keller and Henn worked

collaboratively with the Grammy Award winning group "The Sounds of

Blackness" to create all new songs for the film. The film also featured

the voice talent of actress Alfre Woodard. "John Henry" created a

strong positive response around the animation community, won several film

festivals both domestically and abroad, and was one of seven finalists for the

2001 academy awards in its category.

However, Disney was uneasy about releasing a short about a black folk hero created

by an almost completely white production team, and aside from film festivals,

industry screenings and limited theater screenings required for academy award

consideration, a slightly cut down version of John Henry was released

only as part of a video compilation entitled Disney American Legends in

2001. This became the nation's top-selling children's video for several weeks

upon its release. Disney Educational Productions has also made the film

available as a stand-alone product for video use in schools. And the film is

often shown on The Disney Channel, especially during Black History Month.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HGglKPqG16s

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0SfAJ739rgg&feature=related

Other

Ø

The legend of John

Henry was the inspiration for the third version of the DC Comics superhero

Steel -- also known as John Henry Irons.

Ø

Colson Whitehead's

2001 novel John Henry Days uses the John Henry myth as story background.

Ø

In 1994, They Might Be

Giants released an album, John Henry.

Ø

The story of John

Henry was re-worked in a comic song by the songwriting duo The Smothers

Brothers. In their version, John Henry takes on the steam hammer and is

narrowly defeated, but ends saying 'I'm gonna get me a steam drill too!'

Ø

Gillian Welch's song Elvis

Presley Blues, from the album Time (The Revelator) (2001) compares Elvis

Presley's death to John Henry's.

Ø

Alt-Country legends

Songs: Ohia released the song "John Henry Split My Heart" on their

2003 album, "The Magnolia Electric Co."

Ø

Bart Simpson is forced

to sing "John Henry Was a Steel Driving Man" in the Simpsons episode Homer's

Odyssey.

Ø

The Onion, a satirical

newspaper, ran a fictional story in its February 27, 2006 issue about a

modern-day John Henry. That article, titled "Modern-Day John Henry Dies

Trying to Out-Spreadsheet Excel 11.0," describes an accountant who tried

to prepare a spreadsheet faster than the Microsoft program Excel. Much like the

traditional John Henry, this protagonist won the contest but died afterward.

Ø

In Julian Schnabel's

1996 film Basquiat, Benny (played by Benicio Del Toro) tells the story of John

Henry to Jean-Michel Basquiat (Jeffrey Wright). At the end of the tale Basquiat

replies "But he beat it".

|

In 1972, Michigan sculptor Charles Cooper

completed this eight-foot bronze statue of John Henry. It stands in Memorial

Park above the east portal of the Big Bend Tunnel near Talcott, West

Virginia. |

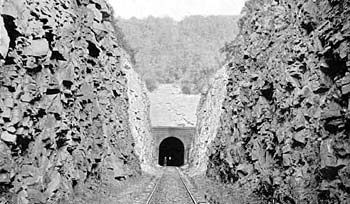

Most accounts have set the ballad of John

Henry at the Big Bend Tunnel, near Talcott in Summers County. Originally

called the Great Bend Tunnel, it was built between 1870-72 for the C & O

Railroad. |

|

The Coosa Tunnel -- one of two railroad

tunnels built in 1887-88 for the Columbus & Western Railroad near Leeds,

Ala., may have been the site of the events in the ballad. Photo:

Fruits of Industry: Points and Pictures along the Central Railroad of Georgia

by A. Pleasant Stovall and O. Pierre Havens, 1895. |

In 1945, Indiana-born illustrator James

Daugherty drew John Henry as a defence worker. |