Battle of Washita River

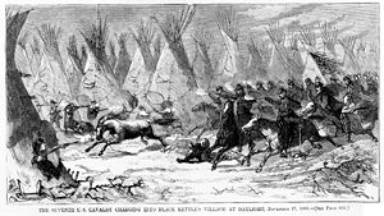

Battle of Washita from Harper's Weekly, December

19, 1868

The Battle of Washita River (or Battle

of the Washita) occurred on November 27, 1868

when Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s 7th U.S. Cavalry attacked Black

Kettle’s Cheyenne camp on the Washita River (near present day Cheyenne,

Oklahoma).

After the signing of the

Medicine Lodge Treaty, the Cheyennes and Arapahoes moved to Indian Territory

(modern Oklahoma) to be in their new reservation. But in the summer

of 1868, after months of fragile peace (with raids between Kaw Indians and

Cheyennes), white settlements in western Kansas, southeast Colorado, and

northwest Texas were hit by raids from war parties of Southern Cheyenne,

Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche, Northern Cheyenne, Brulé and Oglala Lakota, and Pawnee

warriors. Among these raids were those along the Solomon and Saline rivers in

Kansas, commencing on August 10, 1868, during which at least 15 white settlers

were killed, others wounded, and some women raped or taken captive.

On August 19, 1868, Colonel Edward W. Wynkoop, Indian Agent for the Cheyennes and Arapahoes at Fort Lyon, Kansas, interviewed Little Rock, who was a chief in Black Kettle's Cheyenne village. Little Rock gave an account of what he had learned about the raids along the Saline and Solomon rivers. According to Little Rock's account, a war party of about 200 Cheyennes from a camp above the forks of Walnut Creek departed camp intending to go out against the Pawnees, but ended up raiding white settlements along the Saline and Solomon rivers instead. Some of the men responsible for the raids came to Black Kettle's camp, and it was from these men that Little Rock learned what had happened. Little Rock named the men most responsible for the raids and agreed to do his best to have the guilty parties delivered to white authorities.

Indians in

November 1868

Winter camps on the

Washita River

By early November 1868,

Black Kettle's camp joined other Indian camps at the Washita River, which they

knew as Lodgepole River. Overall, a total of about six thousand Indians were in

winter camp along the upper Washita River.

Meanwhile,

the evening before, on November 25, a war party of as many as 150 warriors

which included young men of the camps of Black Kettle, Medicine Arrows, Little

Robe, and Old Whirlwind, had returned to the Washita encampments from raiding

with the Dog Soldiers in the Smoky Hill River country. It was their trail that

Major Joel Elliott of the Seventh Cavalry found on November 26, which

ultimately led Custer's command to the Washita.

Sheridan's offensive

General Philip Sheridan, in command of the U.S.

Army's Department of the Missouri, decided upon a winter campaign against the

Cheyenne raiders. While a winter campaign presented serious logistical

problems, it offered opportunities for decisive results. If the Indians’

shelter, food, and livestock could be destroyed or captured, not only the

warriors but their women and children were at the mercy of the Army and the

elements, and there was little left but surrender.

The Battle

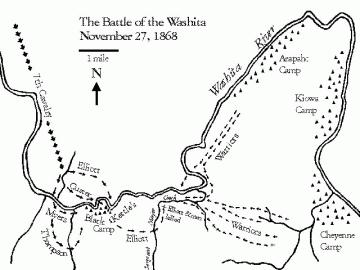

Map of the

battle.

On November 27, 1868 Custer’s Osage Nation scouts

located the trail of an Indian war party. Custer followed this trail all day

without break until nightfall. Upon nightfall there was a short period of rest

until there was sufficient moonlight to continue. Eventually they reached Black

Kettle’s village. Custer divided his force into four parts, each moving into

position so that at first daylight they could all simultaneously converge on

the village. At daybreak the columns attacked, just as Double Wolf awoke and

fired his gun to alert the village; he was among the first to die in the

charge. The Indian warriors quickly left their lodges to take cover behind

trees and in deep ravines. Custer was able to take control of the village

quickly, but it took longer to quell all remaining resistance.

Black Kettle and his

wife, Medicine Woman Later, died while fleeing on a pony, shot in the back. Following

the capture of Black Kettle's village Custer was soon to find himself in a

precarious position. As the fighting was beginning to subside Custer began to

notice large groups of mounted Indians gathering on nearby hilltops. He quickly

learned that Black Kettle's village was only one of the many Indian villages

encamped along the river. Fearing an attack he ordered some of his men to take

defensive positions while the others were to gather the Indian belongings and

horses. What the Americans did not want or could not carry, they destroyed

(including about 675 ponies and horses, 200 horses being given to the

prisoners).

Prior to the battle, Custer had ordered his men take off their greatcoats so they would have greater maneuverability. Rations were also apparently left behind. Custer left a small guard with the coats and rations but the Indian attackers were too numerous and the guard fled, but Indians from the downstream villages who came up to relieve Black Kettle's village were able to capture them.

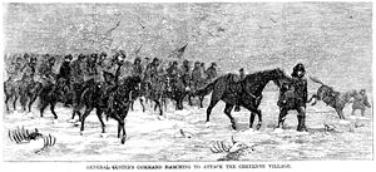

General Custer's command marching to attack the Cheyenne village.

Custer feared the outlying Indians would find and attack his supply train so near nightfall he began marching toward the other Indian encampments. Seeing that Custer was approaching their villages the surrounding Indians retreated to protect their families from a fate similar to that of Black Kettle's village. At this point Custer turned around and began heading back towards his supply train, which he eventually reached. Thus the Battle of Washita was concluded.

Aftermath

From the beginning of

December 1868 the nature of the attack began to be debated in the press. In the

December 9 Leavenworth Evening Bulletin, a story mentioned that:

"Gen. S. Sandford and Tappan, and Col. Taylor of the Indian Peace

Commission, unite in the opinion that the late battle with the Indians was

simply an attack upon peaceful bands, which were on the march to their new

reservations". The December 14 New York Tribune made the following

comment: "Col. Wynkoop, agent for the Cheyenne and Arapahos Indians, has

published his letter of resignation. He regards Gen. Custer's late fight as

simply a massacre, and says that Black Kettle and his band, friendly Indians,

were, when attacked, on their way to their reservation". The scout James

S. Morrison wrote Indian Agent Col. Wynkoop that twice as many women and

children as warriors had been killed during the attack. The Fort Cobb Indian

trader William Griffenstein told Lt. Col. Custer, the 7th U.S. Cavalry had

attacked friendly Indians on the Washita, resulting in General Phillip Sheridan

ordering Griffenstein out of Indian Territory, threatening to hang him if he

returned. The New York Times published a letter describing

Custer as taking "sadistic pleasure in slaughtering the Indian ponies and

dogs" and alluded to killing innocent women and children.

Battle or

massacre?

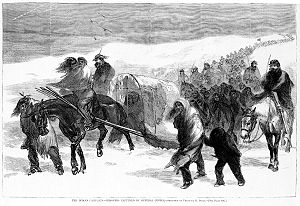

Prisoners captured by General Custer

Custer certainly did not consider Washita a massacre. He does mention that some women took weapons and were subsequently killed. He did leave Washita with women and children prisoners; he did not simply kill every Indian in the village, though he admittedly couldn't avoid killing few women in the middle of the hard fight. Historian Jerome Greene wrote a book about the encounter in 2004, for the National Park Service. He concluded: "Soldiers evidently took measures to protect the women and children." Historian Paul Hutton: "Although the fight on the Washita was most assuredly one-sided, it was not a massacre. Black Kettle's Cheyennes were not unarmed innocents living under the impression that they were not at war. Several of Black Kettle's warriors had recently fought the soldiers, and the chief had been informed by Hazen that there could be no peace until he surrendered to Sheridan. The soldiers were not under orders to kill everyone, for Custer personally stopped the slaying of non-combatants, and fifty-three prisoners were taken by the troops." Historian Joseph B. Thoburn considers the destruction of Black Kettle's village too one-sided to be called a battle. He reasons that had a superior force of Indians attacked a White settlement containing no more people than in Black Kettle's camp, with like results, the incident would doubtless have been heralded as "a massacre."

The Battle of Washita in

film

đ

In the 1970 film Little Big Man, based on

the 1964 novel by Thomas Berger, director Arthur Penn depicted the Seventh

Cavalry's attack on Black Kettle's village on the Washita as a massacre

resembling the My Lai massacre of Vietnamese villagers by U.S. troops during

the Vietnam War.

đ

In the 2003 film The Last Samurai, Tom

Cruise plays Captain Nathan Algren, a veteran of the Seventh Cavalry whose

participation in the Washita action, depicted as a massacre, leaves him haunted

by nightmares.

Sand Creek Massacre

|

|

|

|

Location |

Kiowa

County, Colorado |

|

Date |

November 29, 1864 |

The Sand Creek Massacre (also known as the Chivington

massacre or the Battle of Sand Creek or the Massacre of Cheyenne

Indians) was an incident in the Indian Wars of the United States that

occurred on November 29, 1864, when

Colorado Territory militia attacked and destroyed a village of Cheyenne and

Arapaho encamped in south-eastern Colorado Territory. Based on the oral history

of Southern Cheyenne Chief Laird Cometsevah, around 400 Cheyenne and Arapaho

men, women, and children were killed at Sand Creek. More than 700 American

soldiers were involved.

Background

By the terms of the 1851

Treaty of Fort Laramie, between the United States and the Cheyenne and Arapaho

tribes, the Cheyenne and Arapaho were recognized to hold a vast territory

encompassing the lands between the North Platte River and Arkansas River and

eastward from the Rocky Mountains to western Kansas. However, the discovery in

November 1858 of gold in the Rocky Mountains in Colorado brought on a gold rush

and a consequent flood of white emigration across Cheyenne and Arapaho lands.

Colorado territorial officials pressured federal authorities to redefine the

extent of Indian lands in the territory, and to negotiate a new

treaty. This treaty was the Treaty of Fort Wise; in it, the Cheyenne chiefs and

Arapaho attendees ceded to the United States most of the lands designated to

them by the Fort Laramie treaty. (The Cheyenne chiefs included Black Kettle,

who we know from the later Battle of Washita).

The new reserve, less

than one-thirteenth the size of the 1851 reserve, was located in eastern

Colorado between the Arkansas River and Sand Creek. Some bands of Cheyenne

including the Dog Soldiers, a militaristic band of Cheyennes and Lakotas

that had evolved beginning in the 1830s, were angry at those chiefs who had

signed the treaty, disavowing the treaty and refusing to abide by its

constraints. They continued to live and hunt in the bison-rich lands of eastern

Colorado and western Kansas, becoming increasingly belligerent over the tide of

white immigration across their lands, particularly in the Smoky Hill River

country of Kansas, along which whites had opened a new trail to the gold

fields. Cheyennes opposed to the treaty said that it had been signed by a small

minority of the chiefs without the consent or approval of the rest of the

tribe, that the signatories had not understood what they signed, and that they

had been bribed to sign by a large distribution of gifts. The whites, however,

claimed that the treaty was a "solemn obligation" and considered that

those Indians who refused to abide by it were hostile and planning a war.

The beginning of the

American Civil War in 1861 led to the organization of military forces in

Colorado Territory. In March 1862, the Coloradans defeated the Texas

Confederate Army in the Battle of Glorieta Pass in New Mexico. Following the

battle, the First Regiment of Colorado Volunteers returned to Colorado

Territory and were mounted as a home guard under the command of Colonel John

Chivington. Chivington and Colorado territorial governor John Evans adopted

a hard line against Indians, accused by white settlers of stealing stock.

Conflicts between settlers and Indians in the spring of 1864 included the

capture and destruction of a number of small Cheyenne camps. On May 16, 1864, a

force under Lieutenant George S. Eayre crossed into Kansas and encountered

Cheyennes in their summer buffalo-hunting camp at Big Bushes near the Smoky Hill

River. Cheyenne chiefs Lean Bear and Star approached the soldiers to signal

their peaceful intent, but were shot down by Eayre's troops. This incident

touched off a war of retaliation by the Cheyennes in Kansas.

|

“ |

Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians! ... I

have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any

means under God's heaven to kill Indians. |

” |

|

—- Col. John Milton Chivington, U.S. Army Bury

my heart at Wounded Knee, 1970[ |

||

As conflict

between Indians and white settlers and soldiers in Colorado continued, many of

the Cheyennes and Arapahos were resigned to negotiate peace. They were told to

camp near Fort Lyon on the eastern plains and they would be regarded as

friendly.

Attack

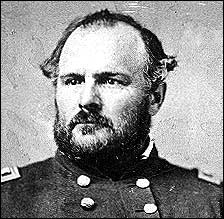

U.S.

Army Colonel John Chivington's portrait. Chivington was a Methodist preacher

and an opponent to slavery.

Black Kettle, a chief of

a group of around 800 mostly Northern Cheyennes, reported to Fort Lyon in an

effort to declare peace. After having done so, he and his band, along with some

Arapahos under Chief Niwot, camped out at nearby Sand Creek, less than 40 miles

north. The Dog Soldiers, who had been responsible for much of the

conflict with whites, were not part of this encampment. Assured by the U.S.

Government's promises of peace, Black Kettle sent most of his warriors to hunt,

leaving only around 60 men and women in the village, most of them too old or

too young to participate in the hunt. Black Kettle flew an American flag over

his lodge since previously he had been assured that this practice would keep

him and his people safe from U.S. soldiers' aggression.

|

“ |

I saw the bodies of those lying there cut all to

pieces, worse mutilated than any I ever saw before; the women cut all to

pieces ... With knives; scalped; their brains knocked out; children two or

three months old; all ages lying there, from sucking infants up to warriors

... By whom were they mutilated? By the United States troops ... |

” |

|

—- John S. Smith, Congressional

Testimony of Mr. John S. Smith, 1865 |

||

Setting out from Fort

Lyon, Colonel Chivington and his 800 troops marched to Black Kettle's campsite.

On the night of November 28, soldiers and

militia drank heavily and celebrated their anticipated victory. Next morning,

Chivington ordered his troops to attack. Disregarding the American flag, and a

white flag that was run up shortly after the soldiers commenced firing,

Chivington's soldiers massacred the majority of its mostly unarmed innocent

inhabitants.

|

“ |

Fingers and ears were cut off the bodies for the

jewelry they carried. The body of White Antelope, lying solitarily in the

creek bed, was a prime target. Besides scalping him the soldiers cut off his

nose, ears, and testicles-the last for a tobacco pouch ... |

” |

|

—- Stan Hoig, The Sand Creek

Massacre, 1974 |

||

Fifteen members of the assembled militias were

killed and more than 50 wounded.

Between the

effects of the heavy drinking and the chaos of the assault, the majority of the

casualties were due to friendly fire. Between 150 and 200 Indians were

estimated killed, nearly all elderly men, women and children (Over 400

children, women, mentally- and physically-challenged, and elders were brutally

murdered according to Southern Cheyenne Chief Laird Cometsevah as based on his

oral history). In testimony before a Congressional committee investigating the

massacre, Chivington reported that as many as 500-600 Indian warriors were

killed. One source from the Cheyenne said that about 53 men and 110 women and

children were killed. Before Chivington and his men left the area, they

plundered the tipis and took the horses. After the smoke cleared, Chivington's

men came back and killed many of the wounded. They also scalped many of the dead,

regardless of whether they were women, children, or babies. Chivington and his

men dressed their weapons, hats and gear with scalps and other body parts,

including human fetuses and male and female genitalia. They also publicly

displayed these battle trophies in Denver's Apollo Theatre and area saloons.

Aftermath

The Sand Creek Massacre

resulted in a heavy loss of life, mostly among Cheyenne and Arapaho women and

children. Hardest hit by the massacre were the Wutapai, Black Kettle's

band. The Dog Soldiers and the Masikota, who by that time had allied, were not

present at Sand Creek. The massacre also devastated the Cheyenne's traditional

power structure, thanks to the deaths of eight members of the Council of

Forty-Four. Among the chiefs killed were most of those who had advocated peace

with white settlers and the U.S. government. The net effect of the murders and

ensuing weakening of the peace faction exacerbated the social and political

rift between the traditional council chiefs and their followers on the one

hand, and the militaristic Dog Soldiers on the other.

Retaliation

After this event many

Cheyenne, including the great warrior Roman Nose, and Arapaho men joined the

Dog Soldiers and sought revenge on settlers throughout the Platte valley.

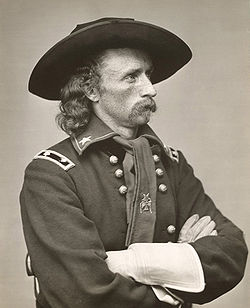

George Armstrong Custer

(December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry

commander in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. At the start of the

Civil War, Custer was a cadet at the United States Military Academy at West

Point, and his class's graduation was accelerated so that they could enter the

war. Custer graduated last in his class and served at the First Battle of Bull

Run on July 21, 1861. Custer established a reputation as an aggressive cavalry

brigade commander willing to take personal risks by leading his Michigan

Brigade into battle, such as the mounted charges at Hunterstown and East

Cavalry Field at the Battle of Gettysburg. In 1865, Custer played a key role in

the Civil War by blocking General Robert E. Lee's retreat on its final day and

received the Flag of Truce at Lee's surrender.

By the end of the Civil War

(April 9, 1865), Custer had achieved the rank of major general of volunteers,

but was reduced to his permanent grade of captain in the regular army when the

troops were sent home. After this demotion, Custer was the commander of the 7th

Cavalry and participated in the Indian Wars. His distinguished war

record, which started with riding dispatches for Winfield Scott, has been

overshadowed in history by his role and fate in the Indian Wars. Custer was

defeated and killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, against

a coalition of Native American tribes composed almost exclusively of Sioux,

Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors, and led by the Sioux warrior Crazy Horse

and the Sioux leaders Gall and Sitting Bull. This confrontation has come

to be popularly known in American history as Custer's Last Stand.

Indian Wars

After the Civil War,

Custer was mustered out of the volunteer service and returned to his permanent

rank of captain in the regular army, assigned to the 5th U.S. Cavalry. Custer

was appointed lieutenant colonel of the newly created U.S. 7th Cavalry

Regiment; later, General Sheridan promoted him major general, whereupon he took

part in expeditions against the Cheyenne in 1867. His career took a brief

detour following the Hancock campaign when he was court-martialed after

abandoning his post to see his wife, and was suspended for duty for one year.

He returned to duty in 1868 to join a winter campaign against the Cheyenne.

Under Sheridan's orders,

Custer led the 7th U.S. Cavalry in an attack on the Cheyenne encampment of Black

Kettle – the Battle of Washita River on November 27, 1868. Custer

reported killing 103 warriors, though estimates by the Cheyenne themselves of

the number of Indian casualties were substantially lower; some women and

children were also killed, and 53 women and children were taken prisoner.

Custer had his men shoot most of the 875 Indian ponies the troops had captured.

This was regarded as the first substantial U.S. victory in the Southern Plains

War, helping to force a significant portion of the Southern Cheyennes onto a

U.S. appointed reservation.

Battle of the Little Bighorn

An

1899 chromolithograph entitled Custer Massacre at Big Horn, Montana — June

25, 1876, artist unknown.

By the time of Custer's

expedition to the Black Hills in 1874, the level of conflict and tension

between the U.S. and many plains Indians tribes had become exceedingly high.

Americans continually broke treaty agreements and advanced further westward,

resulting in violence and acts of depredation by both sides. To take possession

of the Black Hills (and thus the gold deposits), and to stop Indian attacks,

the U.S. decided to corral all remaining free plains Indians. The Grant

government set a deadline of January 31, 1876 for all Sioux and Arapaho

wintering in the "unceded territory" to report to their designated

agencies (reservations) or be considered "hostile".

The 7th Cavalry departed

from Fort Lincoln on May 17, 1876, part of a larger army force planning to

round up remaining free Indians. Meanwhile, in the spring and summer of 1876,

the Hunkpapa Lakota holy man Sitting Bull had called together the

largest ever gathering of plains Indians at Ash Creek, Montana (later moved to

the Little Bighorn River) to discuss what to do about the whites. It was

this united encampment of Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho Indians that

the 7th met at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

|

"Hurrah boys, we've got them! We'll finish

them up and then go home to our station." |

|

—Famous

words reportedly said by General Custer shortly before being killed. |

Initially, Custer had 208 officers and men under

his command, with an additional 142 under Reno, just over a hundred under

Benteen, 50 soldiers with Captain McDougall's rearguard, and 84 soldiers under

Lieutenant Mathey with the pack train. The Indians may have fielded over 1800

warriors. Historian Gregory Michno settles on a low number around 1000 based on

contemporary Lakota testimony, but other sources place the number at 1800 or

2000, especially in the works by Utley and Fox. The 1800–2000 figure is substantially

lower than the higher numbers of 3000 or more postulated by Ambrose, Gray,

Scott and others.

As the troopers were cut

down, the Indians stripped the dead of their firearms and ammunition, with the

result that the return fire from the cavalry steadily decreased, while the fire

from the Indians constantly increased. With Custer and the survivors shooting

the remaining horses to use them as breastworks and making a final stand on the

knoll at the north end of the ridge, the Indians closed in for the final attack

and killed every man in Custer's command. As a result, the Battle of the Little

Bighorn has come to be popularly known as "Custer's Last Stand".

When the main column

under General Terry did arrive two days later, the army found most of the

soldiers' corpses stripped, scalped, and mutilated. Custer's body had two

bullet holes, one in the left temple and one just above the heart. Following

the recovery of Custer's body, he was buried on the battlefield. One year later

Custer's remains and many of his officer's remains were recovered and sent back

east for proper burial.

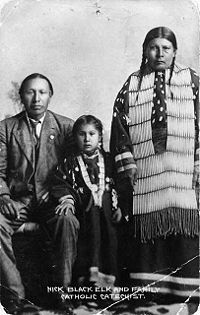

Black Elk

Black Elk with wife and daughter, circa 1890-1910

Heȟáka

Sápa (Black Elk) (c. December 1863 – August 17 or August

19, 1950) was a famous Wičháša Wakȟáŋ

(Medicine Man or Holy Man) of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux). He was Heyoka and a

second cousin of Crazy Horse.

Life

Black Elk participated,

at about the age of twelve, in the Battle of Little Big Horn of 1876,

and was injured in the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. In 1887, Black Elk

traveled to England with Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, an experience he

described in chapter 20 of Black Elk Speaks. Black Elk was baptized,

taking the name Nicholas Black Elk. He continued to serve as a spiritual leader

among his people, seeing no contradiction in embracing what he found valid in

both his tribal traditions concerning Wakan Tanka and those of Christianity. Towards

the end of his life, he revealed the story of his life, and a number of sacred

Sioux rituals to John Neihardt and Joseph Epes Brown for publication, and his

accounts have won wide interest and acclaim. He also claimed to have had

several visions in which he met the spirit that guided the universe. The visions and teachings of Black Elk are honoured and

studied by The National Spiritist Church of Alberta (Native Spirituality

Church) in Canada.

Black Elk Speaks online

http://www.firstpeople.us/articles/Black-Elk-Speaks/Black-Elk-Speaks-Index.html