Film Study: Monty Python's

The Holy Grail

Mr. Steel

The Grail as

depicted in Monty Python's classic comedy

Overview

All students in English

are required by Alberta Learning to engage in a unit of movie analysis and interpretation.

This term, our class will be studying Monty Python's 1975 film, The Holy

Grail. Students will examine the movie on its own merits; however, we will

also study the movie in light of its contributions to comedy, and its mythic

origins in Arthurian legend and medieval literature.

Work and Assessment

A. Students will write a

multiple-choice Movie Terminology Test. This test will evaluate their

understanding of terms relevant to film studies; there will also be some

comprehension questions on the movie itself, and how some of these terms may

help us to appreciate The Holy Grail.

B. Every student will

research and develop a Movie Project/Presentations on The Grail.

Student projects may be done individually, or in groups of up to three.

Movie Projects will respond to ONE of the prescribed thematic questions listed

below. All projects ought to be thoroughly researched, accurately proofread,

and carefully assembled. Projects ought to include textual analysis as well as

visual aids where appropriate. Students will present their movie project to the

class. Projects presentations

will be assessed for their thoroughness in the analysis of themes, as well as

for their effectiveness in oral communication. The use of visuals, audio and/or

multi-media is encouraged.

Project Presentation

Topics:

1. Arthurian Legends: Research one of the

Arthurian knights. Be prepared to tell the class about that knight's quest in

great detail, along with its significance. The knight you choose need not be

one that appears in Python's movie.

2. What is Comedy?: Think about and discuss

what makes something funny. Are there different sorts of humour? Research the

manner in which our understanding of humour differs from culture to culture,

and from generation to generation. Pay particular attention to the differences

between American, British, and Canadian humour. How might we compare and

contrast each? Is part of our identity as Canadians demonstrated through

differences in what we consider to be funny?

3. The image of the quest

in literature: What

is a "quest"? Why are quests popular themes in literature? Why might

quests be an important component of real life as well? Present a book that you

have read to the class in which the symbol of the quest is used. What is the

nature of this quest? What is at stake? What are the components of the quest?

Is the quest successful? Why or why not? What makes a quest successful or not?

4. Modern Re-tellings of

the Grail story: Familiarize

yourself with the original grail story through one of its earliest authors.

Examine a film or a book in which the Grail story is retold (other than

Python's). How is the original story used?

5. Skit Comedy and

Script-Writing: What

makes Python humour unique? For those who are dramatically/comically inclined,

try writing and performing your own Python-esque sketch comedy.

6. Compare and Contrast

Source Texts on the Grail: Choose from among the early accounts of the Grail story, and

recount each of these source tales to the class. Having done so, point out the

similarities and differences between the accounts. What is emphasized, and what

is de-emphasized in each account? Why do you think this is done?

7. The Grail as Symbol: Investigate the various ways

in which the Grail has been viewed symbolically throughout literature and film.

8. The Knights Templar and

the Grail:

Research who were the Knights Templar. What was thought to be special about

them? What were there practices? Where did they live, and how did they live?

What was their supposed relation to the Grail?

9. Joseph of Arimathea: Research who was Joseph

of Arimathea. What significance does he have in the story of the Grail? How

does he figure in the various accounts of this story? Is he prominent in each,

or is he absent in some accounts?

10. Celtic Mythology: Research and present

your findings on the significance of a particular Celtic Myth as it relates to

the unfolding of the Grail legend.

Resources for Research on

The Holy Grail in Literature

(from Wikipedia and The

Catholic Encyclopaedia)

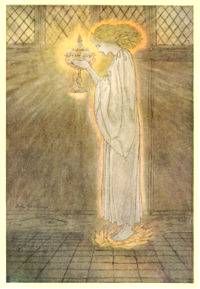

How at the Castle of Corbin a Maiden Bare in the Sangreal and

Foretold the Achievements of Galahad:

illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1917

According

to Christian mythology, the Holy Grail

was the dish, plate, or cup used by Jesus at the Last Supper, said to possess

miraculous powers. Joseph of

Arimathea is said to have received the Grail from an apparition of Jesus, and

he sends it with his followers to Great Britain; building upon this theme, later writers recounted how Joseph used the

Grail to catch Christ's blood while interring him and that in Britain he

founded a line of guardians to keep it safe. The quest for the Holy Grail makes

up an important segment of the Arthurian cycle. The legend may combine

Christian lore with a Celtic myth of a cauldron endowed with special powers.

Origins of the Grail

The Grail plays a different

role everywhere it appears, but in most versions of the legend the hero must

prove himself worthy to be in its presence. In

the early tales, Percival's immaturity prevents him from fulfilling his destiny

when he first encounters the Grail, and he must grow spiritually and mentally

before he can locate it again. In later tellings the Grail is a symbol of God's

grace, available to all but only fully realized by those who prepare themselves

spiritually, like the saintly Galahad.

There are two veins of

thought concerning the Grail's origin. The first holds that the Grail legend derived from early Celtic

myth and folklore. Parallels can be found between Medieval Welsh

literature, Irish material, and the Grail romances. There are similarities

between the Mabinogion's Bran the Blessed and the Arthurian Fisher King,

and between Bran's life-restoring cauldron and the Grail. Other legends

featured magical platters or dishes that symbolize otherworldly power or test

the hero's worth. Sometimes the items generate a never-ending supply of food;

sometimes they can raise the dead. Sometimes they decide who the next king

should be, as only the true sovereign could hold them.

A second view holds that the Grail began as a purely Christian

symbol. For example, 12th century wall paintings from churches present

images of the Virgin Mary holding a bowl that radiates tongues of fire, images

that predate the first literary account of the Grail by Chrétien de Troyes.

Another

recent theory holds that the earliest stories that cast the Grail in a

Christian light were meant to promote the Roman Catholic sacrament of the Holy

Communion. The first Grail stories may have been celebrations of a renewal in

this traditional sacrament. This theory has some basis in the fact that the Grail

legends are a phenomenon of the Western church.

Most scholars today accept that both Christian and Celtic traditions

contributed to the legend's development. The general view is that the central theme of the Grail is Christian,

even when not explicitly religious, but that much of the setting and imagery of

the early romances is drawn from Celtic material.

The

beginnings of the Grail in literature

Chrétien de Troyes

The Grail is first

featured in Perceval, le Conte du Graal (The Story of the Grail) by

Chrétien de Troyes,

who claims he was working from a source book given to him by his patron, Count

Philip of Flanders. In this incomplete

poem, dated sometime between 1180

and 1191, the object has not yet acquired the implications of

holiness it would have in later works. While

dining in the magical abode of the Fisher King, Perceval witnesses a wondrous

procession in which youths carry magnificent objects from one chamber to

another, passing before him at each course of the meal. First comes a young man

carrying a bleeding lance, then two boys carrying candelabras. Finally, a

beautiful young girl emerges bearing an elaborately decorated graal, or

"grail."

Chrétien refers to his object not as "The Grail"

but as un graal, showing the word was used, in its earliest literary

context, as a common noun. For Chrétien the grail was a wide, somewhat deep

dish or bowl that contained a single Mass wafer which provided sustenance for

the Fisher King’s crippled father. Perceval,

who had been warned against talking too much, remains silent through all of

this, and wakes up the next morning alone. He later learns that if he had asked

the appropriate questions about what he saw, he would have healed his maimed

host, much to his honour. The story of the Wounded King's mystical fasting is

not unique; several saints were said to have lived without food besides

communion. This may imply that

Chrétien intended the Mass wafer to be the significant part of the ritual, and

the Grail to be a mere prop.

Robert de Boron

Though Chrétien’s account is the

earliest and most influential of all Grail texts, it was in the work of Robert de Boron that the Grail truly became the

"Holy Grail" and assumed the form most familiar to modern readers. In

his verse romance Joseph d’Arimathie, composed between 1191 and 1202, Robert tells the story of Joseph of

Arimathea acquiring the chalice of the Last Supper to collect Christ’s blood

upon His removal from the cross. Joseph

is thrown in prison where Christ visits him and explains the mysteries of the

blessed cup. Upon his release Joseph gathers his in-laws and other followers

and travels to the west, where he founds a dynasty of Grail keepers that

eventually includes Perceval.

The Grail in other early

literature

After

this point, Grail literature divides into two classes. The first concerns King

Arthur’s knights visiting the Grail castle or questing after the object; the

second concerns the Grail’s history in the time of Joseph of Arimathea.

The

nine most important works from the first group are:

·

The

Perceval of Chrétien de Troyes.

·

Four

continuations of Chrétien’s poem, by authors of differing vision and talent,

designed to bring the story to a close.

·

The

German Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach, which adapted at least the

holiness of Robert’s Grail into the framework of Chrétien’s story.

·

The

Didot Perceval, named after the manuscript’s former owner, and

purportedly a prosification of Robert de Boron’s sequel to Joseph

d’Arimathie.

·

The

Welsh romance Peredur, generally included in the Mabinogion,

likely at least indirectly founded on Chrétien's poem but including very

striking differences from it, preserving as it does elements of pre-Christian

traditions such as the Celtic cult of the head.

·

Perlesvaus, called the "least

canonical" Grail romance because of its very different character.

·

The

German Diu Crône (The Crown), in which Gawain, rather than

Perceval, achieves the Grail.

·

The

Lancelot section of the vast Vulgate Cycle, which introduces the new

Grail hero, Galahad.

·

The

Queste del Saint Graal, another part of the Vulgate Cycle, concerning

the adventures of Galahad and his achievement of the Grail.

Of

the second class there are:

·

Robert

de Boron’s Joseph d’Arimathie,

·

The

Estoire del Saint Graal, the first part of the Vulgate Cycle (but

written after Lancelot and the Queste), based on Robert’s tale

but expanding it greatly with many new details.

·

Though

all these works have their roots in Chrétien, several contain pieces of

tradition not found in Chrétien which are possibly derived from earlier

sources.

Ideas of the Grail

Galahad,

Bors, and Percival achieve the Grail

The

Grail was considered a bowl or dish when first described by Chrétien de Troyes.

Other authors had their own ideas; Robert

de Boron portrayed it as the vessel of the Last Supper, and Peredur had no Grail per se,

presenting the hero instead with a platter containing his kinsman's bloody,

severed head. In Parzival, Wolfram von Eschenbach, citing the

authority of a certain (probably fictional) Kyot the Provençal, claimed the Grail was a stone that fell from

Heaven, and had been the sanctuary of the Neutral Angels who took neither side

during Lucifer's rebellion. The authors of the Vulgate Cycle used the Grail

as a symbol of divine grace.

Galahad, illegitimate son of Lancelot and Elaine, the world's greatest knight

and the Grail Bearer at the castle of Corbenic, is destined to achieve the

Grail, his spiritual purity making him a greater warrior than even his

illustrious father. Galahad and the interpretation of the Grail involving him

were picked up in the 15th century by Sir Thomas Malory in Le Morte d'Arthur,

and remain popular today.

Various notions of the Holy Grail

are currently widespread in Western society (especially British, French and

American), popularized through numerous medieval and modern works and linked

with the predominantly Anglo-French (but also with some German influence) cycle

of stories about King Arthur and his

knights. Because of this wide distribution, Americans and West Europeans

sometimes assume that the Grail idea is universally well known. The stories of the Grail, however, are

totally absent from the folklore of those countries that were and are Eastern

Orthodox (whether Arabs, Slavs, Romanians, or Greeks). This is true of all Arthurian myths, which were not well known east of

Germany until the present-day Hollywood retellings. Nor has the Grail been as popular a subject in some predominantly

Catholic areas, such as Spain and Latin America, as it has been elsewhere. The notions of the Grail, its importance,

and prominence, are a set of ideas that are essentially local and particular,

being linked with Catholic or formerly Catholic locales, Celtic mythology and

Anglo-French medieval storytelling. The contemporary wide distribution of

these ideas is due to the huge influence of the pop culture of countries where

the Grail Myth was prominent in the Middle Ages.

Belief

in the Grail and interest in its potential whereabouts has never ceased.

Ownership has been attributed to various groups (including the Knights Templar, probably because they

were at the peak of their influence around the time that Grail stories started

circulating in the 12th and 13th centuries).

Useful Links:

The

Catholic Encyclopaedia on "The Grail"

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06719a.htm

Le

Morte D'Arthur. Thomas Mallory (online text edition)

http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/Mal1Mor.html

Joseph

of Arimathea

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_of_Arimathea

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08520a.htm

The

Story of the Grail by Chrétien de Troyes

http://www.mcelhearn.com/perceval.html

Robert

de Boron's Joseph of Arimathea

(online text)

http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/4936

Arthurian

Legends

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthurian_legend

Dear

Parents:

All

students in English are required by Alberta Learning to engage in a unit of

movie analysis and interpretation. This term, our class will be studying Monty Python's

1975 film, The Holy Grail. Students will examine the movie on its own merits;

however, we will also study the movie in light of its contributions to comedy,

and its mythic origins in Arthurian legend and medieval literature. Some of the

literary/textual themes we will be exploring through this film include Arthurian legends, the

nature of comedy, comedy as an expression of identity in time and space, quest

imagery in world literature, modern re-tellings of the Grail story, skit comedy

and script-writing, source text analysis, the grail as symbol, the history of

the Knights Templar, as well as both Celtic Mythology and Christian legend and

lore.

As many of you are very

likely familiar with this film, you will remember that it is very silly. There

is little offensive about this film, and it has a PG MPAA rating. However, if

for any reason you do not wish your child to watch this movie as a springboard

into the research topics discussed above, it would certainly be allowable for

your son or daughter to be released from the movie and instead engage in one of

the 10 choice project/presentation topics provided.

Sincerely,

____________________

Sean Steel

BA, BEd, MA, MA