Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin was General Secretary of

the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee. Stalin's

increasing control of the Party from 1928 onwards led to him becoming the de

facto party leader and the dictator of his country; a position which

enabled him to take full control of the Soviet Union and its people.

Under Stalin's leadership, the Soviet Union played a decisive role in the defeat of Nazi Germany in the Second World War (1941-45) and went on to achieve the status of superpower. His crash programs of industrialization and collectivization in the 1930's, World War II casualties, along with his ongoing campaigns of political repression, are estimated to have cost the lives of 5 to 20 million people.

Introduction

Born Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili,

he called himself Joseph Stalin, which meant "Man of Steel".

Stalin became General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party in 1922.

Following the death of Vladimir Lenin, he prevailed in a power struggle

over Leon Trotsky, who was expelled from the Communist Party and

deported from the Soviet Union.

In the 1930s Stalin initiated a Purge of the Communist Party of the Soviet

Union, which has become known as the Great Purge, an unprecedented

campaign of political repression, persecution and executions that reached its

peak in 1937.

Stalin's rule had long-lasting effects on

the features that characterized the Soviet state from the era of his rule to

its collapse in 1991. Stalin claimed his policies were based on Marxism-Leninism.

Now his political and economic system is referred to as Stalinism.

Stalin instituted his Five-Year Plans

in 1928 and collective farming at roughly the same time. The Soviet

Union was transformed from a predominantly peasant society to a major world

industrial power by the end of the 1930s.

Confiscations of grain and other food by

the Soviet authorities under his orders contributed to a famine between 1932

and 1934, especially in the key agricultural regions of the Soviet Union,

Ukraine, Kazakhstan and North Caucasus that resulted in millions of deaths.

Many peasants resisted collectivization and grain confiscations, but were

repressed, most notably well-off peasants deemed kulaks.

Bearing the brunt of the Nazis' attacks

(around 75% of Hitler’s forces), the Soviet Union under Stalin helped to the

defeat of Nazi Germany during World War II (known in the USSR as the Great

Patriotic War). After the

war, Stalin established the USSR as one of the two major superpowers in

the world, a position it maintained for nearly four decades following his death

in 1953.

Stalin's rule, reinforced by a cult of

personality, fought real and alleged opponents mainly through the security

apparatus, such as the NKVD. Millions of people were killed through

famines, executions, deportations, and in the Gulag. Nikita Khrushchev,

Stalin's eventual successor, denounced Stalin's rule and the cult of

personality in 1956, initiating the process of "de-Stalinization".

Stalin adhered to Vladimir Lenin's

doctrine of a strong centralist party of professional revolutionaries. In the

period after the Revolution of 1905, Stalin led "fighting squads"

in bank robberies to raise funds for the Bolshevik Party. His practical

experience made him useful to the party, and gained him a place on its Central

Committee in January 1912.

Joseph Stalin, Vladimir Lenin, and Mikhail Kalinin meeting in 1919 . All three of them were "Old Bolsheviks"; members of the Bolshevik party before the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Rise to power

In 1913 Stalin was co-opted to the

Bolshevik Central Committee. In 1917 Stalin was editor of Pravda,

the official Communist newspaper, while Lenin and much of the Bolshevik

leadership were in exile. Following the February Revolution, Stalin and

the editorial board took a position in favor of supporting Kerensky's

provisional government and, it is alleged, went to the extent of declining to

publish Lenin's articles arguing for the provisional government to be

overthrown.

According to many accounts, Stalin only

played a minor role in the revolution of November 7. The following summary of Trotsky's

Role in 1917 was given by Stalin in Pravda, November 6 1918:

|

“ |

All practical work in connection with the organisation

of the uprising was done under the immediate direction of Comrade Trotsky,

the President of the Petrograd Soviet. It can be stated with certainty that

the Party is indebted primarily and principally to Comrade Trotsky for the

rapid going over of the garrison to the side of the Soviet and the efficient

manner in which the work of the Military Revolutionary Committee was

organised. |

” |

Note: Although this passage was quoted in Stalin's book The

October Revolution issued in 1934, it was expunged in Stalin's Works

released in 1949.

Stalin gained considerable political

power because of his popularity within the Bolshevik party. This took

the dying Lenin by surprise, and in his last writings he famously called for

the removal of Stalin. After Lenin's death, Stalin abandoned the traditional

Bolshevik emphasis on international revolution in favor of a policy of building

"Socialism in One Country", in contrast to Trotsky's theory of

Permanent Revolution.

In the struggle for leadership one thing

was evident: whoever ended up ruling the party had to be considered very loyal

to Lenin. Stalin organized Lenin's funeral and made a speech professing undying

loyalty to Lenin, in almost religious terms. He undermined Trotsky, who

was sick at the time, possibly by misleading him about the date of the funeral.

Thus although Trotsky was Lenin’s associate throughout the early days of the

Soviet regime, he lost ground to Stalin. Stalin made great play of the fact

that Trotsky had joined the Bolsheviks just before the revolution, and

publicized Trotsky's pre-revolutionary disagreements with Lenin. Another event

that helped Stalin's rise was the fact that Trotsky came out against

publication of Lenin's Testament in which he pointed out the strengths and

weaknesses of Stalin and Trotsky and the other main players, and suggested that

he be succeeded by a small group of people.

An important feature of Stalin’s rise to

power is the way that he manipulated his opponents and played them off against

each other. Stalin formed a "troika" of himself,

Zinoviev, and Kamenev against Trotsky. When Trotsky had been eliminated, Stalin

then joined Bukharin and Rykov against Zinoviev and Kamenev.

Stalin gained popular appeal from his

presentation as a 'man of the people' from the poorer classes. The Russian

people were tired from the world war and the civil war, and Stalin's policy of

concentrating in building "Socialism in One Country" was seen

as an optimistic antidote to war.

Stalin took great advantage of the ban on

factionalism which meant that no group could openly go against the policies of

the leader of the party because that meant creation of an opposition. However, Stalin

did not achieve absolute power until the Great Purge of 1936–38.

Stalin and changes in

Soviet society

A. Industrialization

Industrialization or the Industrial

Revolution is a process of social and economic change whereby a human

society is transformed from a pre-industrial (an economy where the amount of capital

accumulated per capita is low) to an industrial state. It is a part of wider

modernisation process

The Russian Civil War and wartime

communism had a devastating effect on the country's economy. Industrial

output in 1922 was 13% of that in 1914. A recovery followed under the New

Economic Policy, which allowed a degree of market flexibility within the

context of socialism. Under Stalin's direction, this was replaced by a system

of centrally ordained "Five-Year Plans" in the late 1920s.

These called for a highly ambitious program of state-guided crash

industrialization and the collectivization of agriculture. Stalin's

government paid for industrialization in the “Five Year Plans” by not

allowing Soviet citizens to spend money, and by stealing wealth from the kulaks.

As a result of Stalin’s Plans, worker's wages dropped to one-tenth of what they

had been before. There was also use of the unpaid labor of both common

and political prisoners in labor camps and the frequent "mobilization"

of communists and Komsomol members for various construction projects. In

spite of early breakdowns and failures, the first two Five-Year Plans achieved

rapid industrialization from a very low economic base. Some suggest that

the Five-Year Plan substantially helped to modernize the previously

backward Soviet economy. New products were developed, and the scale and

efficiency with which existing products were made also greatly increased.

B. Collectivization

Stalin's regime moved to force collectivization

of agriculture. This was intended to increase agricultural output

from large-scale mechanized farms, to bring the peasantry under more direct

political control, and to make tax collection more efficient. Collectivization

meant drastic social changes; people lost control of their land and its

produce. Collectivization also meant a drastic drop in living standards

for many peasants, and it faced violent reaction among the peasantry.

In the first years of collectivization,

agricultural production actually dropped. Stalin blamed

this unanticipated failure on kulaks (rich peasants), who resisted

collectivization. Therefore those defined as "kulaks,"

"kulak helpers," and later "ex-kulaks" were to be shot,

placed into Gulag labor camps, or deported to remote areas of the country,

depending on the charge.

There were massive famines because of

Stalin’s collectivization plans. These famines, some argue, were not

the result of crop failures; rather, it was the excessive demands of the state,

ruthlessly enforced, that cost the lives of as many as five million Ukrainian

peasants. Stalin refused to release large grain reserves that could have

alleviated the famine (and at the same time exporting grain abroad); he was

convinced that the Ukrainian peasants had hidden grain away, and strictly

enforced draconian new collective-farm theft laws in response. The death

toll from famine in the Soviet Union at this time is estimated at between five

and ten million people. The worst crop failure of late tsarist Russia (prior to

Communism) in 1892, caused 375,000 to 400,000 deaths.

The Ukrainian famine (1932-1933),

or Holodomor, was one of the largest national catastrophes with direct

loss of human life in the range of millions (estimates vary).

A child left to starve by Stalin's man made famine

1932-1933.

The Soviet government intended to

eradicate Ukrainian identity, culture, language, and people. Although the

famine affected other regions of the U.S.S.R., its main goal was the

elimination of the Ukrainian nation. Most modern scholars agree that the

famine was caused by the policies of the government of the Soviet Union under

Stalin, rather than by natural reasons, and Holodomor is sometimes referred to

as the Ukrainian Genocide.

Purges and deportations

|

Stalin, as head of the Politburo, took

near-absolute power in the 1930s with a Great Purge of the party, which he

said was needed as an attempt to expel 'opportunists' and

'counter-revolutionary infiltrators'. Those targeted by the purge were often

expelled from the party; however, more severe measures ranged from banishment

to the Gulag labor camps, to execution. Stalin killed,

starved, or worked to death anyone who he percieved to be an enemy or an

opponent. No segment of society was left untouched during the purges. Anyone

accused of "anti-Soviet activities" could be killed or banished to

the Gulag. People would inform on others arbitrarily, to attempt to redeem

themselves, or to gain small retributions. The flimsiest pretexts were often

enough to brand someone an "Enemy of the People," starting the cycle

of public persecution and abuse, often proceeding to interrogation, torture and

deportation, if not death. Millions of people were literally arrested and

killed for nothing.

Shortly before, during and immediately

after World War II, Stalin conducted a series of deportations on a huge

scale which profoundly affected the ethnic map of the Soviet Union. It is

estimated that between 1941 and 1949 nearly 3.3 million were deported to

Siberia and the Central Asian republics. Separatism, resistance to Soviet

rule and collaboration with the invading Germans were cited as the official

reasons for the deportations, rightly or wrongly. Historian Allan Bullock

explains:

|

“ |

Many no doubt had collaborated with the

occupying forces... but many had done so not out of disloyalty but from the

instinct to survive when abandoned to their fate by the retreating Soviet

armies. The individual circumstances were of no interest to Stalin... After

the brief Nazi occupation of the Caucasus was over... the entire population

of five of the small highland peoples of the North Caucasus, as well as the

Crimean Tatars - more than a million souls - (were deported) without notice

or any opportunity to take their possessions. There were certainly

collaborators among these peoples, but most of those had fled with the

Germans. The majority of those left were old folk, women, and children; their

men were away fighting at the front, where the Chechens and Ingushes alone

produced thirty-six Heroes of the Soviet Union. |

” |

During Stalin's rule, all sorts of ethnic groups were deported completely or

partially. Large numbers of Kulaks, regardless of their nationality,

were resettled to Siberia and Central Asia. Deportations took place in

appalling conditions, often by cattle truck, and hundreds of thousands of

deportees died en route. Those who survived were forced to work without

pay in the labour camps. Many of the deportees died of hunger or other

conditions.

Number of victims

Early researchers of the number of people

murdered by Stalin's regime placed the figure between 3 million and 60 million people.

But with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, “evidence” from the

Soviet archives finally became available. The government archives record that

about 800,000 prisoners were executed (for either political or criminal

offences) under Stalin, while another 1.7 million died of privation or other

causes in the Gulags and some 389,000 perished during kulak resettlement - a

total of about 3 million victims. However, many historians do not believe

these numbers, since the Soviets constantly lied about, distorted, and changed

official records and statistics to suit their own purposes. Thus, while

some archival researchers have posited the number of victims of Stalin's

repressions to be no more than about 4 million in total, others believe the

number to be considerably higher. Regardless, it appears that a minimum of

around 10 million surplus deaths (4 million by repression and 6 million from

famine) are attributable to the regime, with a number of recent books

suggesting a probable figure of somewhere between 15 to 20 million. Adding 6-8

million famine victims would yield a figure of between 15 and 17 million

victims. Others, however, continue to maintain that their earlier much higher

estimates are correct.

Religion

A caricature of "Stalin a great friend of religion", when churches were allowed to be opened during World War II.

Stalin's role in the fortunes of the Russian

Orthodox Church is complex. Continuous persecution in the 1930s

resulted in its near-extinction. Over 100,000 priests, nuns, and monks were

shot during the purges of 1937-38. During World War II, however, the Church

was allowed a revival as a patriotic organization.

World War II

Molotov and Stalin.

After the failure of Soviet and Franco-British

talks on a mutual defense pact in Moscow, Stalin began to negotiate a non-aggression

pact with Hitler's Nazi Germany. This pact was called the Molotov-Ribbentrop

Pact. Stalin thought that the Second World War would be the best

opportunity to weaken both the Western nations and Nazi Germany, and to make

Germany suitable for "Sovietization".

Stalin (in background to the right) looks on as Molotov

signs the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

Officially the Pact meant that the Soviets and the

Germans had promised not to attack each other. However, the Molotov-Ribbentrop

Pact had a "secret" annex according to which Central Europe would be

conquered and divided between Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union. Stalin

and Hitler both attacked and conquered various countries according to the terms

of this pact.

In June 1941, Hitler broke the pact and

invaded the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa. Although

expecting war with Germany, Stalin may not have expected an invasion to come so

soon — and the Soviet Union was relatively unprepared for this invasion.

Even though Stalin received intelligence warnings of a German attack, he sought to avoid any obvious defensive preparation which might further provoke the Germans, in the hope of buying time to modernize and strengthen his military forces. In the initial hours after the German attack commenced, Stalin hesitated, wanting to ensure that the German attack was sanctioned by Hitler, rather than the unauthorized action of a rogue general.

The Germans initially made huge advances,

capturing and killing millions of Soviet troops. The Soviet Red Army

put up fierce resistance during the war's early stages, but they were plagued

by an ineffective defense doctrine against the better-equipped, well-trained

and experienced German forces. Stalin feared that Hitler would use

disgruntled Soviet citizens to fight his regime, particularly people imprisoned

in the Gulags. He thus ordered the NKVD to take care of the situation. They

responded by executing hundreds of thousands (perhaps more) of prisoners

throughout the western parts of the Soviet Union. Many others were simply

deported east.

Hitler's experts had expected eight weeks

of war, and early indications appeared to support their predictions. However,

the invading German forces were eventually driven back in December 1941 near

Moscow.

The Big Three: British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Stalin at the Yalta Conference.

Stalin met in several conferences with Churchill and/or Roosevelt in

Moscow, Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam to plan military strategy. His shortcomings

as strategist are frequently noted regarding massive Soviet loss of life and

early Soviet defeats. An example of it is the summer offensive of 1942, which

led to even more losses by the Red Army and recapture of initiative by the

Germans. Stalin eventually recognized his lack of know-how and relied on his

professional generals to conduct the war.

Under Stalin, any Soviet military

commander who allowed retreat without permission from above was subject to

military tribunal. The Soviet soldiers who surrendered were declared traitors;

however most of those who survived the brutality of German captivity were

mobilized again as they were freed. Between 5% and 10% of them were sent to

gulags.

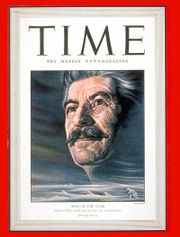

Time magazine (1943-01-04). Time had previously named Stalin

Man of the Year for the year 1939.

In the war's opening stages, the retreating Red Army also sought to deny

resources to the enemy through a scorched earth policy of destroying the

infrastructure and food supplies of areas before the Germans could seize them.

Unfortunately, this, along with abuse by German troops, caused inconceivable

starvation and suffering among the civilian population that were left behind.

According to recent figures, of an

estimated four million POW's taken by the Russians, including Germans,

Japanese, Hungarians, Romanians and others, some 580,000 never returned,

presumably victims of privation or the Gulags, compared with 3.5 million Soviet

POW that died in German camps out of the 5.6 million taken. Returning Soviet

soldiers who had surrendered were viewed with suspicion and some were killed.

The Soviet Union suffered the second highest

number of civilian losses (20 million) yet the highest number of military

losses (at least 8,668,400 Red Army personnel, including around 2 million dead

in Nazi captivity) in World War II. The Nazis considered Slavs in the

Soviet Union to be "sub-human", and made them the target of genocide.

This concept of Slavic inferiority was also the reason why Hitler did not

accept into his army many Soviet citizens who wanted to fight the regime until

1944, when the war was lost for Germany.

Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky was a

Ukrainian-born Jewish Bolshevik revolutionary and Marxist theorist. He was a renowned

public speaker, and an influential politician in the early days of the Soviet

Union. After leading the failed struggle of the Left Opposition against the

policies and rise of Joseph Stalin, Trotsky was expelled from the Communist

Party and deported from the Soviet Union in the Great Purge. He was

eventually assassinated in Mexico by a secret agent working for Stalin.

Trotsky was born with the name Leon

Davidovich Bronstein. He became involved in revolutionary activities in 1896

when he was introduced to Marxism. He helped organize the South Russian

Workers' Union, and using the name 'Lvov', he wrote and printed leaflets and

proclamations, distributed revolutionary pamphlets and popularized socialist

ideas among industrial workers and revolutionary students. Bronstein was caught

and imprisoned in Siberia for his revolutionary activity. He escaped in 1902

and changed his name to Trotsky.

Trotsky moved to London where he met Vladimir Lenin, and worked for

a revolutionary newspaper called Iskra, which was designed to

promote communism. Trotsky soon became one of the paper's leading authors.

Trotsky spent much of his time between 1904 and 1917 trying to reconcile

different groups within the party, which resulted in many clashes with Lenin

and other prominent party members. During these years Trotsky began developing

his theory of permanent revolution.

Trotsky secretly returned to Russia in

February 1905. Trotsky and other Soviet leaders were put on trial in 1906 on

charges of supporting an armed rebellion against the Czar. In January 1907,

Trotsky escaped en route to deportation to Siberia. In October 1908, he started a bi-weekly Russian language Social

Democratic paper aimed at Russian workers called Pravda ("The

Truth"), which was smuggled into Russia. Trotsky continued publishing Pravda

until it finally folded in April 1912.

Trotsky and other communists disagreed

with Lenin’s use of "expropriations" -- armed robberies of banks and

other companies by Bolshevik groups to procure money for the Party.

In January 1912, the majority of the Bolshevik faction led by Lenin

expelled their opponents from the party. Trotsky tried to re-unite the party,

but failed.

World War I (1914-1917) and the Russian Revolution of 1917

Lenin and Trotsky advocated different

internationalist anti-war positions. Trotsky wrote against the war, adopting

the slogan: "peace without indemnities or annexations, peace without

conquerors or conquered". He didn't go quite as far as Lenin, who

advocated Russia's defeat in the war. In September 1916, Trotsky was deported

from France to Spain, and then to the USA for his anti-war activities. Trotsky

was living in New York City when the February Revolution of 1917

overthrew Czar Nicholas II.

Upon returning to Russia, Trotsky sided

with Lenin when the Bolshevik Central Committee discussed staging an armed

uprising and he led the efforts to overthrow the Provisional Government headed

by Aleksandr Kerensky. After the success of the uprising, Trotsky led the

efforts to repel a counter-attack by Cossaks. Allied with Lenin, he

successfully defeated attempts by other Bolshevik Central Committee members to

share power with other socialist parties. By the end of 1917, Trotsky was

unquestionably the second man in the Bolshevik Party after Lenin. The rivalry

between Lenin and Trotsky did much to destroy them both.

After the Russian Revolution

After the Bolsheviks came to power,

Trotsky became the People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs. Trotsky's managerial

and organisation-building skills with the Soviet military were soon tested. The

Bolsheviks were suddenly faced with the loss of most of the country's

territory, an increasingly well organized resistance by Russian anti-Communist

forces (usually referred to as the White Army after their best known

component) and widespread defection by the military experts that Trotsky relied

on.

Trotsky and the Soviet government

responded with a full-fledged mobilization, which increased the size of the Red

Army from less than 300,000 in May 1918 to one million in October 1918, and an

introduction of political commissars into the Red Army. The latter were

responsible for ensuring the loyalty of military experts (who were mostly

former officers in the imperial army) and co-signing their orders.

Facing military defeats in mid-1918,

Trotsky introduced increasingly severe penalties for desertion,

insubordination, and retreat. These reprisals included the death penalty for

deserters and traitors, as well as using former officers' families as hostages

against possible defections. Trotsky also threatened to execute unit commanders

and commissars whose units either deserted or retreated without permission.

Trotsky continued to insist that former

officers should be used as military experts within the Red Army and, in the

summer of 1918, was able to convince Lenin and the Bolshevik leadership not

only to continue the policy in the face of mass defections, but also to give

these experts more direct operational control of the military. In this he

differed sharply from Stalin. Stalin's stubborn opposition to Trotsky's

military policies foreshadowed a continuing acute conflict between the two

Bolsheviks over the policies and direction of the Soviet Union, culminating 10

years later in Trotsky's expulsion from the Soviet Union (and then in his

assassination).

In the meantime, by October 1919 the

Soviet government found itself in the worst crisis of the Civil War.

Trotsky was awarded the Order of the Red Banner for his actions in

Petrograd. Trotsky spent the winter of 1919-1920 in the Urals region trying to

get its economy going again. Based on his experiences there, he proposed

abandoning the policies of War Communism, which included confiscating

grain from peasants, and partially restoring the grain market. Lenin, however,

was still committed to the system of War Communism at the time and the proposal

was rejected. It wasn't until the spring of 1921 that economic collapse and

uprisings would force Lenin and the rest of the Bolshevik leadership to abandon

War Communism in favor of the New Economic Policy.

In late 1921, Lenin's health

deteriorated. Taking advantage of Lenin’s illness, Stalin formed a troika

(triumvirate) with two other leading communists to ensure that Trotsky,

publicly the number two man in the country at the time and Lenin's heir, would

not succeed Lenin. In the fall of 1922, Lenin's relationship with Stalin

deteriorated over Stalin's handling of the issue of merging Soviet republics

into one federal state, the USSR. At

the time of Lenin’s death in 1924, Trotsky was himself recovering from illness

far away from Moscow. Stalin informed him by telegraph of Lenin’s death, but

gave him the wrong information about the date for the funeral. After missing

the funeral, Trotsky was cut off from all power by Stalin.

In 1927, Trotsky was expelled from the

Communist Party and exiled from the Soviet Union in 1929. After Trotsky's

expulsion from the country, his exiled followers (Trotskyists) began to

surrender to Stalin; by doing so, they "admitted their mistakes" and

were reinstated in the Communist Party. However, almost all of them were

murdered in the Great Purges just a few years later.

In August 1936, the first Moscow show

trial was staged in front of an international audience. During the

trial, most of them prominent Old Bolsheviks, confessed to having plotted with

Trotsky to kill Stalin and other members of the Soviet leadership. The

court found everybody guilty and sentenced the defendants to death, Trotsky in

absentia. The second show trial was filled with even more alleged

conspiracies and crimes linked to Trotsky. In 1940, Trotsky was assassinated in

his home by a Stalinist agent, Ramón Mercader, who drove the pick of an ice axe

into Trotsky's skull.

Contributions to theory

Trotsky’s political ideas differed in many respects from those of Stalin.

Unlike Stalin, Trotsky rejected the idea that communism should be established

only in one country; instead, he wanted “permanent revolution" all

around the world in order to spread communism everywhere.

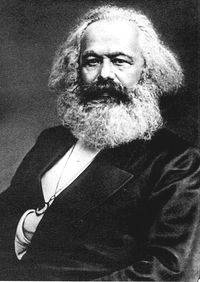

Karl Marx

Karl Marx is most famous for

his analysis of history, summed up in the opening line of the introduction to

the Communist Manifesto (1848): "The history of all

hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles." Marx

believed that capitalism would be replaced by socialism which in

turn would bring communism. Marx is often called the father of

communism. Sometimes, he argued that his analysis of capitalism revealed

that capitalism was destined to end because of unsolvable problems within it:

|

“ |

The development of Modern Industry, therefore,

cuts from under its feet the very foundation on which the bourgeoisie

produces and appropriates products. What the bourgeoisie therefore produces,

above all, are its own grave-diggers. Its fall and the victory of the

proletariat are equally inevitable. |

” |

|

|

— (The Communist

Manifesto) |

|

Other times, he argued that capitalism would end through the organized

actions of an international working class. Marx’s ideas began to exert a major

influence on workers' movements shortly after his death. This influence was

given added impetus by the victory of the Marxist Bolsheviks in the Russian

October Revolution. The relation of Marx to "Marxism" is a

point of controversy.

Karl Marx (along with Friedrich Engels)

envisioned the transformation of the world into a peaceful, equitable place in

which everyone lived in harmony. They thought that this could only occur if

everyone – the rich and the poor, the landowners/businessmen and the

landless/wage-earners -- eventually became part of a single class, the

industrual working class, which they renamed the proletariat. They

thought that other people who talked of fixing the world were dreamers for

assuming that society’s problems could be solved through reason. For Marx and

Engels, real social harmony and equality – the goals of true socialism

-- could only be created if the working man triumphed over the wealthy people

of the world who got rich off of his work. The proletariat, as the “universal

class,” was the future hope of all humanity in Marx’s view; the troubles

that working people experience every day would lead to the destruction of the

current system.

Marx’s emphasis on the importance of

helping the working class makes it sound like, for him, poverty, equality, and

living standards were most important; but this isn’t true. For instance, he

thought that an enforced increase in wages would be nothing more than better

pay for slaves! It wouldn’t make work any more meaningful. What really mattered

to Marx was the problem of alienation. A capitalist, market

system like ours, where we are free to buy and sell what we like for

profit, alienates us from finding meaning in most of our lives. Marx thought

that the capitalist system makes us think backwards about work. In his view, work ought to be precious to

us; it ought to make us feel great; it ought to be an expression of our

creative powers, and it should be our highest activity. Instead, in a

capitalist system, we work not because work itself is a good thing, but because

we have to in order to survive, and in order to make money so we can buy

buy things. We become greedy and

materialistic. We become acquisitive, storing up our purchasing power. As

workers, we lose control over what we produce. We don’t enjoy the “fruits of

our labour,” which are bought and sold on the market, and the profits go to the

boss, not to us. But Marx suggests that even the bosses --property owners and

businessmen -- are equally dehumanized and alienated, even if they don’t suffer

the hardships faced by the proetariat or working class. The social

alienation between owners –Marx calls them the bourgoisie -- and the

workers creates further tension and hatred between the two groups. Marx writes

about how the inequality between these two groups affects each:

Labour certainly produces marvels for the rich but it produces privation for the worker. It produces palaces, but hovels for the worker. It produces beauty, but deformity fore the worker. It replaces labour by machinery, but it casts some of the workers back into a barbarous kind of work and turns the others into machines. It produces intelligence, but also stupidity and cretinism for the workers.

Marx saw the problems of alienation not only in the world of work during

his day; he also thought all of human history could be explained in terms of

this class conflict between the rich few (the bourgeoisie) and the

working many (the proletariat). Because of the inequalities he saw in

the capitialist system, he was certain, not only that capitalism should

be eradicated, but that it would destroy itself through its own internal

contradicitons. Essentially, he thought that the workers of the world would

wise-up and stand united against the bourgeoisie, and that they would take

control of the means of production (all the factories, the businesses,

and the land) away from the bosses and run it communally, sharing out all the

benefits equally among themselves.

Marx and Engels called their doctrine scientific

socialism because they thought that socialism (and ultimately, communism)

was not only the right way to go, but also that their ideas about how a

revolution was coming were bound to happen. Most of their writings analyze the

capitalist or market system looking for what will trigger its self-destruction.

They think that the class-divided market society will, once the working class

become fed-up, give way to a classless society. The workers will take

over all the businesses, and there will be no private property. Everyone will

own everything. With the collective ownership of property, there would

no longer be any real difference between proletarians and bourgeoisie. All

class distinctions will disappear. There will be no more greed, because nobody

will own anything, and it won’t be possible to own anything. Marx thought a

perfect, equal society could be created.

How did Marx think that capitalism would

self-destruct? He was pretty certain that there would be a polarization of

society. That is to say: there would be a huge number of poor,

working-class people, and only a very small number of wealthy owners, or bourgeoisie. The large working class created

by the free-market system would be, who would be the “gravedigger” of the

system. The proletariat would be doomed to poverty, whereas the bourgeoisie

would only become a richer and smaller class. The working class, led by

socialists like Marx, would eventually take over the State and use it to

abolish capitalism. Indeed, when the proletariat masses come to power, they

would find that most of the bourgeoisie were already gone; this is because the

market process would have generated ever larger industrial monopolies; little

owners would have been swallowed up by bigger ones, and those bigger ones by

even bigger and wealthier ones, until only a few giant firms would have

survived the rigours of competition. However, without many

competitors, the market would not work, even on its own terms. The new

Proletarisan State would simply have to take over these monopolies from their

bourgeois owners and set them to work under central planning.

Marx thought the rising up of the working

class would probably happen when unemployment with all its attendant distress

was high among the proletariat; capitalism would destroy itself in a great

crash. Marx was absolutely certain that socialism would overcome capitalism

sometime in the near future. But he didn’t think it was automatic; rather,

he thought it also required a deliberate political struggle. He

proposed (and helped to bring about) the representation of the working class by

organized political parties. He saw two means by which the workers’

party could come to power: evolution or revolution. In constitutional

states with a parliamentry system, he thought that the workers might

struggle to make sure everyone would be allowed to vote, not just those who owned

land. Once the vote was achieved for all, Marx was pretty sure that

socialists could expect to be elected to power, for the proletariat would

be a majority of the electorate; in other words, socialism would be a

natural outgrowth of democracy.

He also thought that socialism might

sometimes require revolution rather than evolution. He proposed a

revolutionary seizure of power, particulary where constitutionalism and the

rule of law did not exist. Such an uprising would produce a workers’

government, the dictatorship of the proletariat. In a situation like

civil war, the proletarian dictatorship would have to ignore the niceties of

the rule of law, at least until its power was secure. Unlike the evolutionary

means where socialist governments could simply be voted into power by the

people, this second approach, where there is no democracy, would involve

violence and bloodshed. These two approaches, united in Marx, would eventually

split into the two mutually antagonistic movements known as socialism

and communism.

What would life be like in a harmonious

communist State after the revolution? Marx gives a rough idea of what he

expects to happen after the workers come to power. There would have to be a

period during which the State would control all property and plan the whole

economy. Even if the State were able to become master of the economy, and

if it could conduct everything through central planning, full equality between

all people would take a long time to achieve. There would have to be an period

during which equality simply meant “equal pay for equal work.” All

workers would be employed by the state, and ownership of property would no

longer allow the wealthy to escape labour; but some would work more effectivey

and diligently than others, and they would be rewarded for doing so. Beyond

this stage, Marx’s thoughts on the future become pretty wishy-washy. The

state would lose its coercive character; that is, it wouldn’t need to use force

to make people behave properly, since all greed would have been wiped out with

the eradication of private property. This only makes sense if we accept

the premise that human quarrels are fundamentally caused by privtate property;

a classless society would therefore not need a state to maintain civil peace.

It was also Marx’s view that the State was always the tool that one class used

to dominate others, so by definition a classless society swould be a

stateless society. The state would “wither away.” People would learn

to live without the need for any kind of government. Once the state was no

longer needed, people wouldn’t need to be paid for their work. The idea of “equal

work for equal pay” would give way to a nobler form of equality in the

words, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.”

At this advanced stage of development, alienation will have ended. Work

would become a freely creative activity performed for its own sake, not to be

bought and sold. People would express themselves in all directions, utilizing their creativity.

Vladimir Lenin

Lenin’s dad died when he was a young boy;

his eldest brother was arrested and hanged for participating in a terrorist

bomb plot threatening the life of the Czar, and his sister was also banished

because of her association. This event radicalized Lenin, and his official

Soviet biographies describe it as central to the revolutionary track of his

life. As Lenin became interested in Marxism, he was involved in student

protests and was subsequently arrested. He was then expelled from Kazan

University for his political ideas, but he continued to study independently,

however. Lenin moved to St. Petersburg in 1893, where he became increasingly

involved in revolutionary propaganda efforts, joining the local Marxist group.

He co-founded the newspaper Iskra. Lenin was active in politics

and, in 1903, led the Bolshevik faction of the Marxist Russian Social

Democratic Labour Party.

When the First World War began in

1914, Lenin opposed Russia’s involvement. He believed that the peasants were

fighting the battle of the bourgeoisie for them, and he adopted the stance that

what he described as an "imperialist war" ought to be turned

into a civil war between the classes. He looked at the war, and thought it was

the result of western imperialism; that is, he thought that the rich

European countries were simply fighting for territories in which to markt their

own goods on the grounds that their own home markets had become saturated.

The 1917 February Revolution in Russia and the overthrow of Czar Nicholas

II caught Lenin by surprise. He realized that he must return to Russia as soon

as possible, but this was problematic, since the First World War would make

travel home very difficult and dangerous. He managed to return to Petrograd in

October, inspiring the October Revolution with the slogan "All

Power to the Soviets!" Lenin directed the overthrow of the Provisional

Government, marking the beginning of Soviet rule.

In 1917, Lenin was

elected as the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars by the Russian

Congress of Soviets. His first concern was to take Russia out of the First

World War. In 1918, Lenin removed Russia from World War I by agreeing to

the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, under which Russia lost significant territories

in Europe.

After the Bolsheviks lost the elections

for the Russian Constituent Assembly, they used the Red Guards to shut down the

first session of the Assembly. This marked the beginning of the steady

elimination from political life of all factions and parties whose views did not

correspond to the position taken by Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

To protect the newly-established Bolshevik government from

counterrevolutionaries and other political opponents, the Bolsheviks created a secret

police, the Cheka. Censorship was quickly imposed, and it was up

to the Cheka to confiscate the literature of dissident workers.

Lenin and the Red Terror

After a botched assassination attempt

against Lenin, Stalin, in a telegram to Lenin, argued that a policy of

"open and systematic mass terror" be instigated against "those

responsible". Lenin and the other Bolsheviks agreed; they instructed the

Cheka to commence a "Red Terror." Between 1918-21 up to

200,000 were executed.

By September 1921, there were more than 70,000 people sent to forced labour

camps due to the Red Terror. Lenin had always been an advocate of "mass

terror against enemies of the revolution" and was open about his view

that the proletarian state was a system of organized violence against the

capitalist establishment. The terror, while encouraged by the Bolsheviks,

had its roots in a popular anger against the privileged. When other Bolshevik

leaders tried to curb the "excesses" of the Cheka in late 1918 during

the Terror, it was Lenin who defended it. Lenin remained an advocate of mass

terror.

Russian Communist Party and civil war

In 1919, Lenin and other Bolshevik

leaders met with revolutionary socialists from around the world and formed the Communist

International. Members of the Communist International, including Lenin and

the Bolsheviks themselves, broke off from the broader socialist movement. From

that point onwards, they would become known as communists. In Russia, the

Bolshevik Party was renamed the "Russian Communist Party.”

Meanwhile, the civil war raged across

Russia. A wide variety of political movements and their supporters took

up arms to support or overthrow the Soviet government. Although many

different factions were involved in the civil war, the two main forces were the

Red Army (communists) and the White Army (traditionalists). Foreign

powers such as France, Britain, the United States and Japan also intervened in

this war (on behalf of the White Army), though their impact was peripheral at

best. Eventually, the more organizationally proficient Red Army, led by

Leon Trotsky, won the civil war, defeating the White Russian forces and their

allies in 1920. Smaller battles continued for several more years, however. The

civil war has been described as one "unprecedented for its savagery,"

with mass executions and other atrocities committed by both sides. Between

battles, executions, famine and epidemics, many millions would perish.

Lenin was a harsh critic of imperialism. In 1917 he

declared the unconditional right of self-determination and separation for

national minorities and oppressed nations. However, when the Russian Civil

War was won he used military force to assimilate the newly independent states

of Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. He argued that the

inclusion of those countries into the newly emerging Soviet government would

shelter them from capitalist imperial ambitions.

During the civil war, as an attempt to

maintain food supply to the cities and the army in the conditions of economic

collapse, the Bolsheviks adopted the policy of war communism. That

involved "requisitioning" supplies from the peasantry for little or

nothing in exchange. This led the peasants to drastically reduce their

crop production. The resulting conflicts began with the Cheka and the army

shooting hostages, and ended with a second full-scale civil war against the

peasantry, including the use of poison gas, death camps, and deportations. In

1920, Lenin ordered increased emphasis on the food requisitioning from the

peasantry, at the same time as the Cheka gave detailed reports about the large

scale famine. The long war and a drought in 1921 also contributed to the

famine. Estimates on the deaths from this famine are between 3 and 10 million.

The long years of war, the Bolshevik

policy of war communism, the Russian famine of 1921, and the encirclement of

hostile governments took their toll on Russia, however, and much of the country

lay in ruins. There were many peasant uprisings. In 1921, Lenin replaced the

policy of War Communism with the New Economic Policy (NEP), in an

attempt to rebuild industry and especially agriculture. The new policy was

based on a recognition of political and economic realities, though it was

intended merely as a tactical retreat from the socialist ideal. The whole

policy was later reversed by Stalin.

Lenin’s final days, his death, and mummification

Lenin's health had been severely damaged by the strains of revolution and

war. The assassination attempt earlier in his life also added to his health

problems. The bullet was still lodged in his neck, too close to his spine for

medical techniques of the time to remove. In May 1922, Lenin had his first

stroke. Of Stalin, who had been the Communist Party's general secretary

since April 1922, Lenin said that he had "unlimited authority

concentrated in his hands" and suggested that "comrades think about a

way of removing Stalin from that post." Lenin died in 1924. The city of

Petrograd was renamed Leningrad in his honor three days after Lenin's

death. This remained the name of the city until the collapse and liquidation of

the Soviet Union in 1991, when it reverted to its original name, St

Petersburg. His body was embalmed and placed on permanent exhibition in the

Lenin Mausoleum in Moscow. Lenin’s character was

elevated over time to the point of near religious reverence. By the 1980s,

every major city in the Soviet Union had a statue of Lenin in its central

square, either a Lenin street or a Lenin Square near the center, and often 20

or more smaller statues and busts throughout its territory.

The Difference Between Marxism and Leninism

The Russian Empire was ruled

autocratically by the Czar; the absence of a parliament and constitution

there made it impossible to bring about socialist reforms through democratic

means. The Russian Social Democratic Party was forced to work illegally,

secretively, and conspiratorially. Because conditions were so different in

Russia from those in western Europe where members of socialist parties had been

elected to parliaments by free votes, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, the leader

of the Bolsheviks, was led by these conditions to create a new style and

a new threory of party leadership. Before Lenin, Karl Marx had expected that

the revolution would occur all-of-a-sudden from the spontaneous class

consciousness of the workers; the proletariat – or working class – would just

get fed up with the rich bourgeoisie owners and take over in a revolution.

However, in Russia Lenin faced a backward country and a small working class. He

was certain that any idea of revolution would’t rise from the poor workers; he

himself would have to lead the charge. This seemingly minor difference

implied a new approach to the problems of party organization. The party had

to be firmly controlled from the top because the leadership could not rely on

the workers’ sponatneity. Lenin’s theory of the disciplined party – democratic

centralism – moulded the party into an effective revolutionary weapon that

was especially suited to survival in the autocratic Russian setting.

Lenin’s socialist ideas are different

from Marx in another way as well: Marx always thought that the socialist

revolution would be a world revolution.

Marx thought that the European nations would drag their empires with them into

socialism. Because he emphasized Europe, Marx thought the the revoultion would

occur soon because capitalism, which was fated to put an end to itself, was well-advanced

on that continent. Marx certainly expected that the world-wide proletariat

would have victory over the few bourgeoisie within his own lifetime. But when

the First World War broke out, Marx had already been dead for thirty years and

the socialists still had not come to power anywhere!

Lenin didn’t take this as evidence that

Marx was wrong and that the whole idea that communism was inevitable was

stupid. Rather, he decided that the “advanced nations” had managed to postpone

the revolution by conquering huge colonial empires. Where Marx thought that

the capitalist countries of Europe would over-produce themselves into

bankruptcy, Lenin believed that they had escaped this problem by finding

markets for their products in other countries held in their economic power, who

would have to buy their goods. However, Lenin was sure that this

“imperialst solution” could only be temporary because the world was finite and

now totally subdivided. Sooner or later, the problems of capitalist

competitiveness would cause the system to self-destruct. Lenin thought that

World War I showed that the imperialists had begun to qualrrel with each other.

He believed that the socialist revolution would arise not from a business

crash, as Marx had been inclined to

believe, but out of the turnoil of war. Lenin thus broadened the scope

of socialism from a European to a global movement, and in doing so

bolstered his own revolutionary optimism. “Capitalism,” he wrote, “has grown

into a world system of colonial oppression and of the financial strangulation

of the overwhelming population of the world by a handful of ‘advanced’

contries.”

World War I marked the end of the Second

International – the international socialist organization headed by Engels.

Although socialists had prided themselves on their internationalism, everyone

felt obligated to fight on behalf of their own country. Most of the workers in

the combatant states supported the war effort, effectively pitting the

International against itself. The successful socialist revolution in Russia was

welcomed by socialists all around the world.

In February 1917, the Czar was toppled and a constitutional democracy

created. However, in October of the same year, the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin,

seized control of the state through insurrections of armed workers in St.

Petersburg and Moscow. The Bolsheviks then created a dictatorship of the

proletariat in which their party played the dominant role. They outlawed

political oppostion – even socialist opposition. These events were an

agonizing test for the socialists of Western Europe, who had yearned for a

revolution for generations. Now they were witnessing a sucessful one, and they

were appalled by its undemocratice aspects.

The eventual result of the Russian Revolution was an

irreparable split in the world socialist movement. Those who approved of Lenin and his methods formed

communist parties in every country and gathered themselves in the Third

International, or Comintern (short for “Communist International”).

The official ideology of these parties was now Marxism as modified by Lenin,

or Marxist-Leninism. In practice, the Comintern soon became an

extension of the Soviet state for foreign policy purposes. It was dissolved in

1943 by Stalin as a gesture of cooperation with the Allies during WWII.

The individual communist parties continued to be closely tied to Moscow, but

the organizational emphasis shifted to Soviet satellite states. In 1947 there

were bound together into the Cominform (Communist Information Bureau),

which in 1956 was in turn replaced by the Warsaw Treaty Organization.

The latter was dissolved in 1991 as part of the general decommunizaiton of

Eastern Europe.

The Russian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution of 1917 was a series of political and social

upheavals in Russia, involving first the overthrow of the czarist autocracy,

and then the overthrow of the liberal and moderate-socialist Provisional

Government, resulting in the establishment of Soviet power under the

control of the Bolshevik party. This eventually led to the establishment of

the Soviet Union, which lasted until its dissolution in 1991.

The Russian Revolution of 1917

centers around two primary events: the February Revolution and the October

Revolution. The February Revolution, which removed Tsar (also spelled

Czar) Nicholas II from power, developed spontaneously out of a series of

increasingly violent demonstrations and riots on the streets of Petrograd

(present-day St. Petersburg), during a time when the tsar was away from the

capital visiting troops on the World War I front.

Though

the February Revolution was a popular uprising, it did not

necessarily express the wishes of the majority of the Russian population, as

the event was primarily limited to the city of Petrograd. However, most of

those who took power after the February Revolution, in the Provisional

Government (the temporary government that replaced the tsar) and in

the Petrograd Soviet (an influential local council representing workers and

soldiers in Petrograd), generally favored rule that was at least partially

democratic.

The October

Revolution (also called the Bolshevik Revolution) overturned the

interim Provisional Government and established the Soviet Union. The

October Revolution was a much more deliberate event, orchestrated by a small

group of people. The Bolsheviks, who led this coup, prepared their coup in

only six months. They were generally viewed as an extremist group and had very

little popular support when they began serious efforts in April 1917.

By October, the Bolsheviks’ popular base was much larger; though still a

minority within the country as a whole, they had built up a majority of support

within Petrograd and other urban centres.

After October, the Bolsheviks

realized that they could not maintain power in an election-based system without

sharing power with other parties and compromising their principles. As a

result, they formally abandoned the democratic process in January 1918

and declared themselves the representatives of a dictatorship of the

proletariat. In response, the Russian Civil War broke out in the

summer of that year and would last well into 1920.

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War lasted from

1917 to 1921. It began immediately after the collapse of the Russian

provisional government and the Bolshevik takeover of Petrograd, rapidly

intensifying after Lenin's dissolution of the Russian Constituent Assembly and

the Trotsky-negotiated signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

Although the war was multi-sided and

included foreign forces from several countries, the main hostilities took

place between Communist forces, known as the Red Army, and

loosely-allied anti-Bolshevik forces, known as the White Army.

The most intense years of fighting took place from 1918 to 1920. The

Communists won after four years of intense fighting, and the result was the

country in ruins and the establishment of the Soviet Union in 1922.

Following the fall of Czar Nicholas II

of Russia and the turbulent Russian Revolution throughout 1917, a

socialist-leaning Provisional Government was established. In October

another revolution occurred in which the Red Guard, armed groups of

workers and deserting soldiers directed by the Bolshevik Party, seized control

of Saint Petersburg (then known as Petrograd) and began an immediate armed

takeover of cities and villages throughout the former Russian Empire. In

January 1918, Lenin had the Constituent Assembly violently dissolved, proclaiming

the Soviets as the new government of Russia.

The Bolsheviks decided to immediately

make peace with the German Empire and the Central Powers, as they

had promised the Russian people prior to the Revolution. Leon Trotsky,

representing the Bolsheviks, refused at first to sign the treaty while

continuing to observe a unilateral cease fire, following the policy of "No

fighting, but no peace treaty". In view of this, the Germans began an all

out advance on the Eastern Front, encountering no resistance. Signing a formal

peace treaty was the only option in the eyes of the Bolsheviks, because the

Russian army was demobilized and the newly formed Red Guard were

incapable of stopping the advance. They also understood that the impending

counterrevolutionary resistance was more dangerous than the concessions of

the treaty, which Lenin viewed as temporary in the light of aspirations for a

world revolution. The Soviets acceded to a peace treaty and the formal

agreement, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, was signed in 1918.

In the wake of the October Revolution,

the old Russian army had been demobilized and the volunteer based Red

Guard was the Bolsheviks' main military arm. In January, Trotsky headed its

reorganization into the "Workers' and Peasants' Red Army," in order

to create a more professional fighting force. He instituted a forceful

conscription program, frequently resorting to repressive tactics, and used

former Tsarist officers as "military specialists". The Bolsheviks

banned all non-Bolshevik political activity around the same time, even other

socialist groups, when it became clear that the Bolsheviks could not hold a

majority of the seats in any democratically elected governing body outside of

St. Petersburg and Moscow. While resistance to the Red Guard began on the

very next day after the Bolshevik coup, the Brest-Litovsk treaty and the

political ban became a catalyst for the formation of anti-Bolshevik groups both

inside and outside Russia, pushing them into action against the new regime.

A loose confederation of anti-Bolshevik

forces aligned against the Communist government. Their military forces became

known as the White movement (sometimes referred to as the "White

Army"), and they controlled significant parts of the former Russian

empire for most of the war. The Western Allies, upset at the withdrawal of

Russia from the war effort and worried about a possible Russo-German alliance,

also expressed their dismay at the Bolsheviks. Winston Churchill

declared that Bolshevism must be "strangled in its cradle". In

addition, there was a concern, shared by many Central Powers as well, that the

socialist revolutionary ideas would spread to the West. Hence, many of these

countries expressed their support for the Whites, occasionally providing

troops and supplies. In addition, volunteers from Italy and Poland also joined

the Whites.

The majority of the fighting ended in 1920 with the defeat of the White

Army.

Aftermath of the Civil War

The results of the civil war were

momentous. Russia had been at war for seven years, during which time some

20,000,000 of its people had lost their lives (to go with the 3,000,000

surrendered to Poland). The civil war had taken an estimated 15,000,000 of

them, including at least 1,000,000 soldiers of the Russian Red Army and more

than 500,000 White soldiers who died in battle. 50,000 Russian Communists were

killed by the counter-revolutionary Whites, and 250,000 civillians were wiped

out by the Cheka (secret police). At the end of the Civil War, Soviet Russia

was exhausted and near ruin. The droughts of 1920 and 1921, as well as the 1921

famine, worsened the disaster still further. Disease had reached pandemic

proportions, with 3,000,000 dying of typhus alone in 1920. Millions more were

also killed by widespread starvation, wholesale massacres by both sides, and

even pogroms against Jews in Ukraine and southern Russia. The economic loss to

Soviet Russia was 50 billion rubles, or 35 billion in current U.S. Dollars. The

industrial production value descended to one seventh of the value of 1913, and

agriculture to one third. The economy had been devasted.

The Hammer and Sickle

The symbol as it appeared on the Soviet flag

The hammer and sickle is a symbol used to represent communism

and communist political parties. It features a hammer superimposed on a

sickle, or vice versa. The two tools are symbols of the peasantry and

the industrial proletariat; placing them together symbolises the unity

between agricultural and industrial workers.

It is best known from having been incorporated into the red flag of the

Soviet Union, along with the Red Star. It has also been used in other flags and

emblems.

The Soviet Flag

Worker and Kolkhoz Woman

The hammer and sickle was originally a

hammer crossed over a plough, with the same meaning (unity of peasants and

workers) as the more well known hammer and sickle. The hammer and sickle,

though in use since 1917/18, was not the official symbol until 1922, before

which the original hammer and plough insignia was used by the Red Army and the

Red Guard on uniforms, medals, caps, etc.

Some anthropologists have argued that the

symbol, like others used in the Soviet Union, was actually a Russian

Orthodox symbol that was used by the Communist Party to fill the religious needs

that Communism was replacing as a new state "religion." The

symbol can be seen as a permutation of the Russian Orthodox two-barred cross.

Russian Orthodox Cross

Proletariat

The proletariat (from Latin proles, offspring) is a term used to identify

a lower social class; a member of such a class is proletarian. Originally it

was identified as those people who had no wealth other than their sons; the

term was initially used in a derogatory sense, until Karl Marx used it

as a sociological term to refer to the working class.

The Proletariat in Marxist theory

In Marxist theory, the proletariat is

that class of society which does not have ownership of the means of production. Proletarians

are wage-workers. Marxism sees the proletariat and bourgeoisie

(capitalist class) as occupying conflicting positions, since (for

example) factory workers automatically wish wages to be as high as possible,

while owners and their proxies wish for wages (costs) to be as low as possible.

According to Marxism, capitalism

is a system based on the exploitation of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie

(the "capitalists", who own and control the means of

production). This exploitation takes place as follows: the workers, who

own no means of production of their own, must seek jobs in order to live. They

get hired by a capitalist and work for him, producing some sort of goods or

services. These goods or services then become the property of the capitalist,

who sells them and gets a certain amount of money in exchange. One part of

the wealth produced is used to pay the workers' wages, while the other part

(surplus value) is split between the capitalist's private takings (profit), and

the money used to pay rent, buy supplies and renew the forces of production. Thus

the capitalist can earn money (profit) from the work of his employees without

actually doing any work, or in excess of his own work. Marxists argue

that new wealth is created through work; therefore, if someone gains wealth that

he did not work for, then someone else works and does not receive the full

wealth created by his work. In other words, that "someone else" is

exploited. Thus, Marxists argue that capitalists make a profit by exploiting

workers.

Marx himself argued that it was the goal

of the proletariat itself to displace the capitalist system with socialism,

changing the social relationships underpinning the class system and then

developing into a communist society in which: "..the free development of

each is the condition for the free development of all" (Communist

Manifesto).

Communism

Communism is an ideology that seeks to

establish a classless, stateless social organization based on common ownership

of the means of production. It can be considered a branch of the broader

socialist movement.

Karl Marx held that society

could not be transformed from the capitalist mode of production to the

advanced communist mode of production all at once, but required a transitional

period which Marx described as the revolutionary dictatorship of the

proletariat, the first stage of communism. The communist society Marx

envisioned emerging from capitalism has never been implemented, and it remains

theoretical; Marx, in fact, commented very little on what communist society

would actually look like.

In the late 19th century, Marxist

theories motivated socialist parties across Europe, although their policies

later developed along the lines of "reforming" capitalism, rather than

overthrowing it. One exception was the Russian Social Democratic Labour

Party. One branch of this party, commonly known as the Bolsheviks

and headed by Vladimir Lenin, succeeded in taking control of the country

after the toppling of the Provisional Government in the Russian

Revolution of 1917. In 1918, this party changed its name to the Communist

Party, thus establishing the contemporary distinction between communism and

other trends of socialism.

Communism grew out of the socialist movement of 19th century Europe. As the

Industrial Revolution advanced, socialist critics blamed capitalism

for the misery of the proletariat—a new class of poor, urban factory workers

who labored under often-hazardous conditions. Foremost among these critics

were the German philosopher Karl Marx and his associate Friedrich Engels.

Marxism

Like other socialists, Marx and Engels

sought an end to capitalism and the systems which they perceived to be

responsible for the exploitation of workers. But whereas earlier socialists

often favored longer-term social reform, Marx and Engels believed that

popular revolution was all but inevitable, and the only path to socialism.

According to the Marxist argument for

communism, the main characteristic of human life in class society is alienation;

and communism is desirable because it entails the full realization of human

freedom. Marx believed that communism allowed people to do what they want,

but also put humans in such conditions and such relations with one another that

they would not wish to exploit, or have any need to.

Marxism holds that a process of class conflict and

revolutionary struggle will result in victory for the proletariat and the

establishment of a communist society in which private ownership is abolished

over time and the means of production and subsistence belong to the community. Marx himself

wrote little about life under communism, giving only the most general

indication as to what constituted a communist society. It is clear that it

entails abundance in which there is little limit to the projects that humans

may undertake. In the popular slogan that was adopted by the communist

movement, communism was envisioned as a world in which each gave according

to their abilities, and received according to their needs.

Leninism

In Russia, the 1917 October Revolution was the first time any party

with an avowedly Marxist orientation, in this case the Bolshevik

Party, seized state power. The assumption of state power by the Bolsheviks

generated a great deal of practical and theoretical debate within the Marxist

movement. Marx believed that socialism and communism would be built upon

foundations laid by the most advanced capitalist development. Russia, however,

was one of the poorest countries in Europe with an enormous, largely illiterate

peasantry and a minority of industrial workers. The Bolsheviks successful

rise to power was based upon the slogans "peace, bread, and land" and

"All power to the Soviets," slogans which tapped the massive public

desire for an end to Russian involvement in the First World War, the peasants'

demand for land reform, and popular support for the Soviets.

The usage of the terms

"communism" and "socialism" shifted after 1917, when the Bolsheviks

changed their name to the Communist Party and installed a single-party

regime devoted to the implementation of socialist policies under Leninism.

The Second International had dissolved in 1916 over national divisions,

as the separate national parties that composed it did not maintain a unified

front against the war, instead generally supporting their respective nation's

role. Lenin thus created the Third International (Comintern) in 1919.

Henceforth, the term "Communism" was applied to the objective

of the parties founded under the umbrella of the Comintern. Their

program called for the uniting of workers of the world for revolution, which

would be followed by the establishment of a dictatorship of the proletariat as

well as the development of a socialist economy. Ultimately, if their

program held, there would develop a harmonious classless society, with the

withering away of the state.

During the Russian Civil War

(1918-1922), the Bolsheviks nationalized all productive property and

imposed a policy of "war communism," which put factories and railroads

under strict government control, collected and rationed food, and introduced

some bourgeois management of industry. After three years of war, Lenin declared

the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921, which was to give a "limited

place for a limited time to capitalism." The NEP lasted until 1928,

when Joseph Stalin's personal fight for leadership, and the introduction

of the first Five Year Plan spelled the end of it. Following the

Russian Civil War, the Bolsheviks formed in 1922 the Union of Soviet Socialist

Republics (USSR), or Soviet Union, from the former Russian Empire.

Marxism-Leninism

Marxist-Leninism is a version of

socialism, with some important modifications, adopted by the Soviet Union under

Stalin. It shaped the Soviet Union and influenced Communist Parties worldwide. It

was heralded as a possibility of building communism through a massive program

of industrialization and collectivization. The rapid

development of industry, and above all the victory of the Soviet Union

in the Second World War, maintained that vision throughout the world. The

Communist Party of the Soviet Union adopted the Marxist-Leninist theory of

"socialism in one country" and claimed that, due to the

"aggravation of class struggle under socialism," it was possible,

even necessary, to build socialism alone in one country, the USSR. This line

was challenged by Leon Trotsky, whose theory of "permanent

revolution" stressed the necessity of world revolution.

The NKVD (Secret

Police)

The NKVD or People's

Commisariat for Internal Affairs was the leading secret police

organization of the Soviet Union that was responsible for political

repressions during Stalinism. It ran the Gulag system of forced labor;

itdeported Russian populations and peasants labeled as "Kulaks"

to unpopulated regions of the country; it guarded state borders and conducted espionage;

it executed political assassinations abroad and was responsible for

subversion of foreign governments, and enforcing Stalinist policy within

Communist movements in other countries.

Although the NKVD performed the function

of state security, the name of the organization today is associated

primarily with its criminal activities: political repressions and assassinations,

military crimes, violations of the rights of Soviet and foreign

citizens, and violation of the law.

Repressions and executions

The NKVD arrested, exiled, tortured, or

killed anyone accused of being an “enemy of the people.” Millions were

rounded up and sent to gulag camps and hundreds of thousands were executed

by the NKVD. Formally, most of these people were convicted by NKVD troikas